The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture

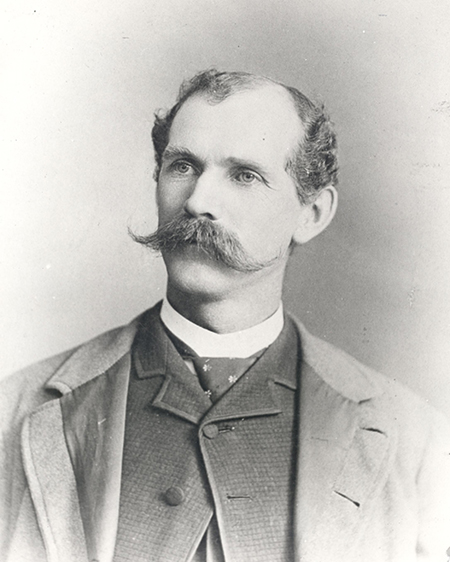

COUCH, WILLIAM LEWIS (1850–1890).

A leader of the Boomer Movement and the eldest child of Meshach H. and Mary Bryan Couch, William Lewis Couch was born November 20, 1850, in Wilkes County, North Carolina. After the Civil War ended, M. H. Couch moved the family to Kansas, and there William grew to manhood. While receiving only a rudimentary education, he was always an avid reader. Couch married his sweetheart, Cynthia Gordon, a Quaker eight years his senior. In 1871 the couple located in Butler County near Douglass, Kansas, and purchased a farm. After the railroad extended its lines from Emporia to Wichita, Couch followed the line and took advantage of many business opportunities. He became a fixture in the Wichita business community after 1874, selling grain, operating an elevator, trading and selling horses and mules, and running a combination hardware and grocery store. However, a change in markets, coupled with other financial setbacks, cost him much of his hard-earned fortune. After losing the grocery store and paying many of his outstanding debts, he was financially depleted. Nevertheless, he still adequately provided for his family, deriving a steady income from the livestock business.

In fall 1879, after hearing David L. Payne talk about the "free land" available for homesteads in the "Oklahoma Country," Couch became a follower of the boomer leader. Payne was most convincing about the fertility of soil, abundance of game, and other wonders of the land. Couch made several financial contributions to Payne's colony, helping to fund the fledgling enterprise, and became familiar with the country, learning the choice locations where he could claim his future homestead. Couch believed Payne's assertion that these were public lands free for the taking, despite government warnings to the contrary. The family returned to Douglass, Kansas, in 1882 so that William could be closer to his father. The elder Couch looked after the family while his son became more active in Payne's colony. By that time the family had grown to five children: Ira, Minnie Alice, Eugene, Perley, and Albert.

Couch's service to the boomers earned him a leadership position. In early February 1883 he led the "Camp Alice" expedition to the Oklahoma country after the boomers' earlier settlement ventures had failed. This attempt, too, failed when the army arrived, arrested the would-be settlers, and placed them under guard at Fort Reno. Couch entered the forbidden land again in August 1883 and in April 1884. During the April 1884 trip Meshach Couch staked a claim near the present University of Oklahoma Health Sciences complex in Oklahoma City.

David Payne's untimely death on November 28, 1884, thrust Couch into sole leadership of the boomers, a roll he did not want. After Payne's funeral the colonists held an emergency meeting and elected Couch their president. The new leader made plans for the next intrusion. By December 8, 1884, Couch had assembled a force of three hundred ready to proceed to Oklahoma from a starting point in Kansas. The throng traveled in the harsh winter weather to a place called "Stillwater," camping at a stream later dubbed Boomer Creek. They set up their winter camp and awaited the inevitable confrontation with the U.S. Army. Lt. M. W. Day had orders to expel them, but the boomers were determined to carry out the wishes of the fallen Payne. Couch was determined they would not fail. Outnumbered, the officer sent for reenforcement, including two artillery pieces, and informed Couch that he and his men would be fired upon if they did not leave within two days. Eventually Couch relented, and the would-be settlers broke camp and dispersed. Nevertheless, the desire to open the forbidden land did not subside even though Couch and some of his followers were subsequently arrested and charged with treason against the United States.

Couch and his men were freed after government witnesses failed to appear against them. Like Payne, Couch could not, and would not, accept defeat. He and many others continued to press Congress for opening the land, and after four years the House of Representatives approved the "Oklahoma Bill" on February 1, 1889. Attached to the Indian Appropriations Bill for that year, the measure passed on the last day of the session. Pres. Grover Cleveland signed the bill two days before Benjamin Harrison succeeded him. The proclamation for the land opening was set for noon April 22, 1889, ending the long struggle of Payne and Couch.

Like David Payne, William Couch did not hold on to the land he sought for a homestead. Although he made the land run, staked his claim on property in present downtown Oklahoma City, and was elected the city's first mayor, he did not live to receive title to the property, nor did his widow or his heirs. Couch was shot by J. C. Adams on April 4, 1890, and died of his wound on April 21. Couch's claim was disputed by several other claimants, and title was awarded to Robert W. Higgins. Many of the boomers did not get title to the land they had worked so desperately to get. Couch finished the work Payne started. Without the efforts of both these men, it would have taken years longer to open the land for white settlement.

See Also

CHARLES C. CARPENTER, SAMUEL CROCKER, LAND RUN OF 1889, DAVID LEWIS PAYNE, SETTLEMENT PATTERNS, UNASSIGNED LANDS