The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture

MUSKOGEE COUNTY.

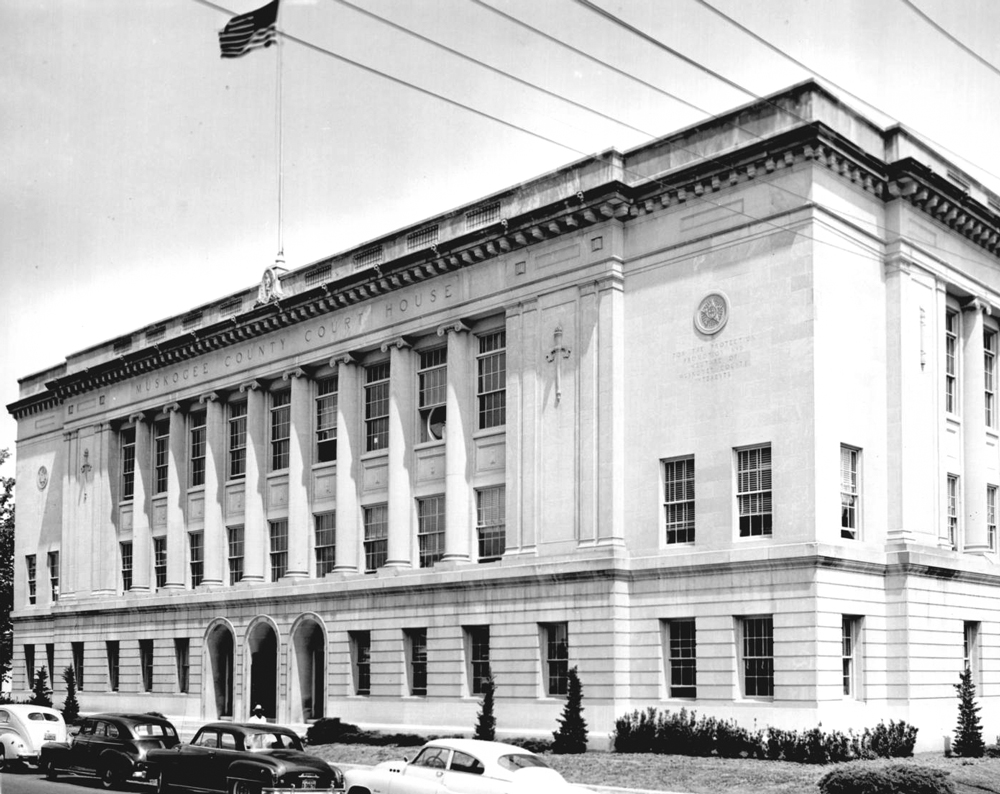

Located in eastern Oklahoma, Muskogee County was named for the Muscogee (Creek) Tribe, although its boundaries encompass the Muskogee District of the Creek Nation and a portion of the Illinois and Canadian districts of the Cherokee Nation. Wagoner and Cherokee counties on the north, Cherokee and Sequoyah counties on the east, Haskell and McIntosh counties on the south, and Okmulgee and McIntosh counties on the west border this county. The city of Muskogee, established in 1872, serves as the county seat. In addition to Muskogee, incorporated towns include Boynton, Braggs, Council Hill, Fort Gibson, Haskell, Oktaha, Porum, Summit, Taft, Wainwright, Warner, and Webber Falls.

Three important rivers, the Arkansas, Verdigris, and Neosho (Grand), converge in Muskogee County. The county includes 838.99 square miles of land and water that encompass a varied topography. The western portion is primarily prairie grassland growing over a layer of sandstone that contains pockets of coal, oil, and natural gas. The prairie gives way to the wooded Cookson Hills in the county's eastern section, which is on the western fringe of the Ozark Mountains. The confluence of the Arkansas, Verdigris, and Neosho gave the area the name of Three Forks, and several salt springs attracted abundant game to the region.

Although prehistoric sites, mainly surface finds, date to the Paleo-Indian period (prior to 6,000 B.C.), archaeological studies have focused on the Caddoan stage (A.D. 300 to 1200). These Native people, known as the Mound Builders, left a legacy in the ceremonial mounds that can still be seen along riverbanks. In 1719 Jean Baptiste Bénard de la Harpe, a French explorer and trader, encountered a Wichita village in the present county. By the end of the eighteenth century a settlement of fur traders emerged at the Three Forks, including Auguste Pierre Chouteau, one of the area's earliest frontier merchants. By the early 1800s the Osage had become the region's dominant tribe, driving out the less warlike Wichita. However, Cherokee and Choctaw hunting forays into the area challenged the Osage, resulting in frequent conflict. In response, in 1824 federal officials established Fort Gibson on the Grand River at the Three Forks. The town of Fort Gibson, which emerged near the post, is the county's oldest.

Fort Gibson became the terminus of the Trail of Tears for the Cherokee and Creek people. Removed from their homeland in the southeastern United States, many settled along the rivers of Muskogee County. They founded only a few small towns such as Webbers Falls. Some Creek and Cherokee reestablished their cotton plantations and continued to use slave labor.

With the outbreak of the Civil War Confederate troops of both the Cherokee and Creek nations established Fort Davis across the Arkansas River from Fort Gibson. At Fort Gibson regiments of the Cherokee and Creek Home Guard as well as the First Kansas Colored Infantry held Indian Territory for the Union. In 1862 Federal troops captured and destroyed Fort Davis. Other engagements that occurred in the county included the Bayou Menard Skirmish (1862), several at Webbers Falls (1862), and the Creek Agency Skirmish (1863). At the war's conclusion the Creek Nation's plantation lifestyle ended. Creek Freedmen returned to the river bottoms within the county and raised cotton.

Following the war the Five Tribes signed new treaties with the federal government. In these they gave up western lands and agreed to allow railroad rights-of-way. In 1871 the Missouri, Kansas and Texas Railway (MK&T) crossed Indian Territory, paralleling the route of the Texas Road. Reaching the Three Forks area in fall 1871, the railroad intended to build a depot at the site of Fort Davis. Finding the terrain unsuitable, workers constructed the depot further south and named it Muscogee Station. In 1872 the town of Muskogee (originally spelled Muscogee) developed around the depot. Eleven miles south, the town of Oktaha was also established on the MK&T rail line that year.

Other important developments affected the area. In 1874 federal officials consolidated the agencies to the Five Tribes into one, Union Agency, and located it in the Creek Nation just west of Muskogee. This decision solidified Muskogee as the center of federal activity in Indian Territory. In 1889 a federal district court was established there. During these years outlaw gangs terrorized the people of Indian Territory and fled into the Cookson Hills in eastern Muskogee County. One of the most colorful frontier outlaws was Belle Starr, whose homestead lay near Briartown in southern Muskogee County. In 1882 a political rift within the Creek tribe led to the Green Peach War, a conflict that saw little bloodshed but created much unrest in the area.

In 1894 the Dawes Commission to the Five Tribes established its headquarters at Muskogee. The commission undertook the enormous task of negotiating new treaties, enrolling tribe members, and assigning individual land allotments. It also brought a large influx of federal employees. In addition, many Freedmen received allotments in Muskogee County. As a result, a number of historically All-Black towns were founded, including Chase (later Beland), Lee, Summit, Twine (present Taft), and Wybark.

Railroads continued to build into the territory, and a number of new lines soon crossed the area. These included the Kansas and Arkansas Valley Railway (1888, later the Missouri Pacific Railway), the Midland Valley Railroad (1904–05), the Ozark and Cherokee Central Railway (1901–03, sold to the St. Louis and San Francisco Railway, Frisco), the Shawnee, Oklahoma and Missouri Coal and Railway (1902–03, sold to the Frisco), the Muskogee Union Railway (1903–04, sold to the Missouri, Oklahoma and Gulf Railway, or MOG), and the MOG (1903–05, which became the Texas and Pacific Railroad). The towns of Haskell, Boynton, Taft, Porum, Council Hill, Keefeton, Warner, and Wainwright emerged along the new railroads.

At the turn of the twentieth century conflict between two ranching families in the southern part of the county turned violent. Known as the Porum Range War, the feud between the Davis and Hester families continued for several years. Frequently a train carload of deputy marshals was summoned from Muskogee to restore order in the Porum vicinity.

In 1905 Muskogee hosted a statehood convention at which Indian Territory delegates wrote a constitution to create the State of Sequoyah. Ratified by the voters, the constitution was submitted to Congress, which rejected it. The next year many Muskogee County leaders participated in the 1906 Constitutional Convention at Guthrie. Charles N. Haskell chaired the committee that established county boundaries and county seats for the new state, including Muskogee County.

At 1907 statehood Muskogee County was one of the largest in population but, with the exception of the city of Muskogee, had few large towns. The area was predominantly agricultural, with corn, cotton, and wheat the principal crops. Ranching, primarily beef cattle, was another significant industry. Agricultural service industries included cotton gins, grain mills, and stockyards. Cotton production declined dramatically during the 1930s and was replaced by soybeans, wheat, feed grains, and grasses. Truck farming became profitable during and after World War II, fostering the development of a canning and food-processing industry. John T. Griffin brought Griffin Grocery Company to the county, leading the business to become a large wholesale grocery distributor and manufacturer of food products. Griffin also was a pioneer in developing Oklahoma's radio and television industry.

Other economic activities included oil, gas, and coal production, but these activities never reached the levels achieved in other regions. Sand and gravel pits, along with brick and glass manufacturing, developed and remained important employment sources. O. W. Coburn built an optical business that became one of the largest in the nation and employed hundreds of workers. Other industrialists included the Buddrus family, who began Acme Engineering, and the Rooney family, who founded Manhattan Construction. State and federal employment has long been important, primarily in education and veterans' services. Light manufacturing and health care as well as social services provide jobs for residents. The town of Taft has two state correctional facilities, Dr. Eddie Warrior Correctional Center for women and Jess Dunn Correctional Center for men.

Military training during World War II brought a significant increase in both population and job opportunities. Camp Gruber, built in 1942 near Braggs in the Cookson Hills, served as a U.S. Army training base. Camp Gruber remains an active Oklahoma National Guard base. Hatbox Field and Davis Field in Muskogee prepared aviators for the war.

Transportation emerged as an important feature for the county. Steamboats had plied the Arkansas River throughout much of the nineteenth and early twentieth century. The McClellan-Kerr Arkansas River Navigation System, dedicated in 1971, opened the Arkansas and Verdigris rivers to year-round commercial traffic and fostered the development of the Port of Muskogee. A north-south main line of the Union Pacific Railway bisects the county. U.S. Highway 69 and Interstate Highway 40 are heavily traveled thoroughfares, and the Muskogee Turnpike crosses the county from north to south. State Highways 2, 10, 16, 62, 64, 71, 72, 104, and 165 are also important routes.

Education became a prominent element of development. Early schools were operated by the Creek and Cherokee nations, and other schools were private enterprises started by churches or individuals. In 1880 Bacone College, Oklahoma's oldest, began as Indian University in Tahlequah but was moved to the Creek Nation in present Muskogee County in 1885. Connors State College was established at Warner in 1909. The Indian Capital Technical Center opened in Muskogee in 1970. Evangel Mission, a school at Union Agency for Creek Freedmen, operated in the 1880s, and the building eventually became home to the Five Civilized Tribes Museum in Muskogee. In 1898 a facility for educating visually impaired people opened at Fort Gibson. Later moved to Muskogee, it became the Oklahoma School for the Blind. Minerva Home, a school for girls in Muskogee, became Henry Kendall College in 1894. That institution later moved to Tulsa and became the University of Tulsa. In 1994 Northeastern State University opened a branch campus in Muskogee.

Many Muskogee County natives have played important roles in history. Stand Watie, a Cherokee from Webbers Falls, rose to the rank of brigadier general in the Confederate army and was its last general to surrender at the close of the Civil War. In 1875 Bass Reeves became one of the first African Americans appointed as a deputy U.S. marshal west of the Mississippi River. He served the federal court in Muskogee. Pleasant Porter, principal chief of the Creek Nation, negotiated the allotment treaty with the Dawes Commission. A wealthy rancher and respected tribal leader, he served as president of the Sequoyah Convention. Alexander Posey, a Creek poet and newspaper editor in Muskogee, served as secretary of the Sequoyah Convention and is credited with writing most of that constitution. Historians Grant and Carolyn Foreman, considered the foremost authorities of the history of the Five Tribes, together wrote more than twenty-five books.

Numerous significant political figures began their careers in Muskogee County. Originally from Ohio, railroad developer Charles N. Haskell settled in Muskogee in 1901 and became a leader at the Sequoyah Convention and Oklahoma's first governor in 1907. Robert L. Owen, a Cherokee, served as the U.S. agent to the Five Tribes in Muskogee. In 1907 he became one of Oklahoma's first U.S. senators. Alice M. Robertson, the first woman appointed postmaster of a Class A post office in the United States, in 1920 was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives. She was the second woman in the United States to hold a congressional seat and was the only woman to serve Oklahoma in Congress until 2006. The Edmondsons of Muskogee became a prominent political family. James Howard Edmondson served as Oklahoma governor (1959–63) and as U.S. senator (1963–64). Edmond Edmondson served the Second Congressional District, which includes Muskogee County, from 1953 to 1973. His son Drew Edmondson was elected attorney general of Oklahoma. Mike Synar served in Congress from 1979 to 1995. He was succeeded by another Muskogeean, Tom Coburn, elected to the U.S. Senate in 2004.

Muskogee County had 37,467 residents at 1907 statehood and rapidly grew to 52,743 in 1910. The county then settled into a steady growth rate, reaching 61,710 in 1920 and 66,424 in 1930 but dropping to 65,914 in 1940. A population surge occurred during the years when Camp Gruber operated, but after the war ended, many people left. In 1950 the census revealed a population of 65,573. The number of residents declined to 61,866 in 1960 and 59,542 by 1970, but by 1980 the figure had rebounded to 67,033. In 1990 the census counted 68,078 and in 2000, 69,451. In 2010 Muskogee County's 70,990 residents were 59.8 percent white, 17.5 percent American Indian, 11.3 percent African American, and 0.6 percent Asian. Hispanic ethnicity was identified as 5.2 percent. In April 2020 the population of 66,344 were 53.9 percent white, 20.6 percent American Indian, 10.4 percent African American, 1.0 percent Asian, and 7.7 percent Hispanic.