Commerce in Oklahoma

The Settler Economy

The tribal governments in Indian Territory were dismantled with purpose. The United States government deliberately stripped away tribal sovereignty to take advantage of the land and resources. After opening the area to white settlement, statehood became an inevitability. Without representation in the federal government, the tribes and their members were overridden and ignored. Non-Native settlers quickly organized the western half of Indian Territory as Oklahoma Territory. White citizens of the United States had an advantage over the tribal leaders and more opportunities to exercise their power to shape the formation of the state.

Railroads expanded to cross Indian Territory, further dividing the land previously communally owned. The railroads were used to promote a primary economy. Farmers produced raw materials, which were shipped to other places to be manufactured into different items. In the southern part of the state, cotton remained a major crop, and farms of various sizes became dedicated to growing it. This led to problems for landowners with smaller plots and lower incomes. A lack of crop diversity resulted in an overreliance on the cotton market. If the cotton market failed, these farmers would be left without money for food or supplies.

Cotton field in Muskogee (image courtesy National Museum of the American Indian).

Cotton harvest (image courtesy National Museum of the American Indian).

Workers’ unions had come to the area with the railroads and grew quickly as the region moved towards statehood. Mining unions were some of the strongest and most active in the area, given the particularly dangerous jobs the miners took on and the low pay they often received. Some national labor organizations refused to include tenant farmers or sharecroppers, but farmer’s unions grew in strength and became major influences in politics of the early 20th century. Unions were diverse and stretched across nearly every industry and ethnic group. The Farmers’ Alliance and trade unions grew in strength as the population of the area increased. Months after the Enabling Act cleared the path to statehood, several labor organizations worked together to write the Shawnee Demands. The Shawnee Demands proposed 24 ways for the state constitution to protect the working class. This included compulsory education, regulated work days, and anti-corruption measures. A major goal of the Shawnee Demands was to use government power to prevent unfair treatment of workers. Agreeing to some or all of these popular demands provided support from lower-class voters to politicians and instilled progressive ideas into the state constitution. When many of these voters were later disenfranchised by literacy tests, their political influence waned.

With statehood came divisive political practices. Jim Crow laws and disenfranchisement tactics replaced the fluidity of race relations during the territorial era. Previously established All-Black towns were now facing white encroachment and additional discrimination. More strictly enforced segregation solidified distinct communities not only culturally, but economically as well. Business centers like the Greenwood District in Tulsa found success and created wealth and strong Black communities. The new ideas and successful businesses of these communities often faced increased discrimination from hate-fueled groups such as the Ku Klux Klan.

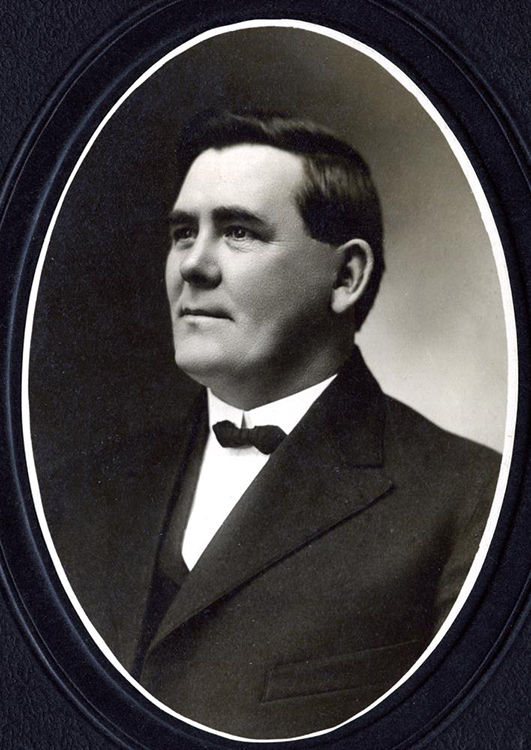

A major figure in union organizing, the Shawnee Demands, and early Oklahoma politics was Peter Hanraty (4566, Frederick S. Barde Collection, OHS).

Mann Grocery Store in Greenwood (image courtesy Greenwood Cultural Center).

Statewide, progressive ideas were still common, and many Oklahomans embraced socialism. The Socialist Party of Oklahoma was one of the strongest in the nation and advocated for workers and fair business practices. With a large working class, voters advocated for their own protection legally and economically.

Socialists in Oklahoma adapted practices, such as religious encampments, to advance their goals. Photograph by Tom M. Greenwood, September 2-5, 1910 (20489, OHS Photo Collection, OHS).

Corn, cotton, and wheat remained the largest crops in the area, with cotton taking a substantial lead in monetary value and opportunity. The lack of crop diversification continued to pose a threat, and although agriculture remained very influential, individual farmers faced increasing hardships. Many were tenant farmers and lacked the security land that ownership promised. Sharecropping, or tenant farming, involves a landlord who owns the farmland and an individual farmer who pays for their rent by working the land and handing over up to two-thirds of their crop. Sharecropping became more and more common, with two-thirds of African American farmers and more than half of white farmers renting the land they worked by 1935. This worsened the problem of overproduction of a single crop because landowners demanded tenants plant as much of the dominant cash crop as possible. The Oklahoma economy was relying on unstable markets. Mining, oil, and farming industries all require a strong balance of supply and demand. Consumers and producers face economic hardship when this balance is not achieved, and the entire state’s economy is at risk.

Sharecroppers in Muskogee, photograph by Russell Lee, 1939 (image courtesy Library of Congress).

The petroleum industry boomed in the early 20th century. Discoveries were made in every corner of the state, and Oklahoma quickly became a leader in oil production. Tulsa was known as “the Oil Capital of the World.” Cushing produced a massive percentage of the country’s oil. Geological processes were reinvented and improved nationwide because of developments made in Oklahoma. A massive employer with far-reaching political and economic influence, the oil industry drew migrants to the Oklahoma area.

Laying an oil pipeline (21639.5, Oklahoma Historical Society Photograph Collection, OHS).

Oil meter, 1920 (20218.3558, Clayton E. Soule Collection, OHS).

A wooden oil well, 1930 (18785, Oklahoma Historical Society Photograph Collection, OHS).

Other mining ventures, such as coal, were also large sources of employment for the state, but wouldn’t stretch into the 21st century as the oil industry did. Coal and other minerals led to the creation of mining towns, with populations that fluctuated and relied on the nearby mines. Many modern cities, such as McAlester, began as mining towns. Mining strikes were particularly common, starting as early as 1894. Strikes are opportunities for employees to demand fair treatment from their employers, whether it is adequate pay or safety-related regulations. Workers withhold their labor until an agreement is met. Unions gave the working class the ability to present their concerns as a unified and organized front, and they continue to serve that purpose today.

As World War I began in Europe, the Central Powers’ markets were closed to American exporters because of the embargo, specifically devastating the cotton market. The closure of these markets gave rise to widespread antiwar sentiments as farmers found themselves with excessive supply and lowered demand. The possibility of entering the war worried the general population for several reasons, but the economic consequences were a primary issue. As America prepared to join the war, other markets opened for excess cotton, such as military uniforms. This increase in demand helped balance the market, resulting in a rare and profitable period for Oklahoma farmers.

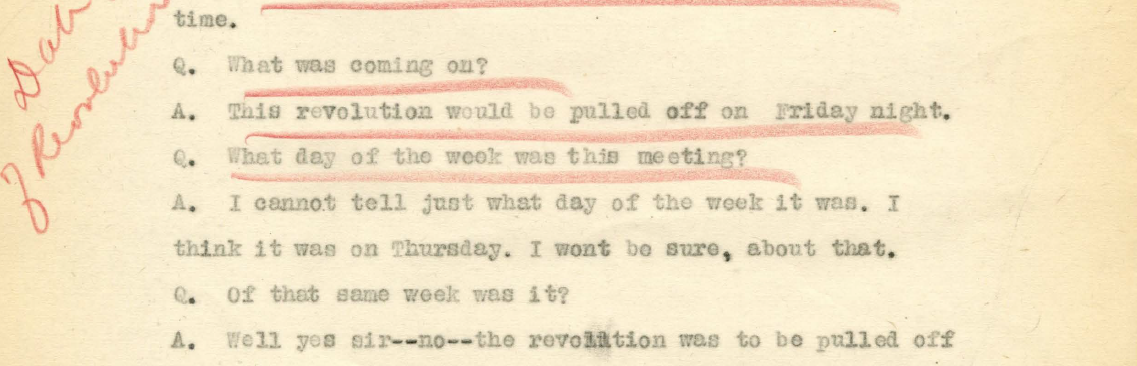

At the same time, antiwar sentiments continued with the new wartime demands and worries of loss of labor to military recruitment and drafts. These frustrations came to a climax in the Green Corn Rebellion of 1917, where hundreds of working-class Oklahomans of various races and trades gathered in protest. After hundreds of arrests and four deaths, the rebellion was quelled by a hastily organized posse. Vigilante justice was still common in this era and was often politically or racially motivated. Anyone expressing “anti-American” ideas was persecuted legally and sometimes violently. This eventually led to the dissolution of many progressive groups, including the Socialist Party of Oklahoma and some labor organizations.

The Green Corn Rebellion was just one example of the working class rallying for a cause, whether it was their inclusion in the state constitution or the many strikes and protests that occurred in the early 20th century. World War I provided a historic period of wealth for Oklahoma farmers. After the war, the agricultural markets quickly declined without the wartime demands. Coal demands remained high, but miners’ pay was reduced to prewar numbers, leading to more discontent among the workers and a series of strikes. Oil discoveries and innovations continued, but the industry and the government would face the harsh necessity of a balance between supply and demand when the Great Depression began.

Portion of the testimony from United States v. Clure Isenhouer et al., the trial related to the Green Corn Rebellion, 1917 (image courtesy National Archives).