The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture

FOLK ARCHITECTURE.

Architectural traditions encompass not only the types of structures designed and built, but also the ways in which buildings are arranged upon the land, the methods and materials of construction, the functions that different structures serve, and the social, cultural, economic, and political milieu associated with particular architectural conventions. The term "folk architecture" is often used to draw a distinction between popular or landmark architecture and is nearly synonymous with the terms "vernacular architecture" and "traditional architecture." Therefore, folk architecture includes those dwellings, places of worship, barns, and other structures that are designed and built without the assistance of formally schooled and professionally trained architects.

Folk architecture differs from popular architecture in several ways. For example, folk architecture tends to be utilitarian and conservative, reflecting the specific needs, economics, customs, and beliefs of a particular community. Folk architecture also represents a community's cumulative wisdom about solutions to particular problems. For this reason, folk architectural traditions are organic in that they have changed over time to suit a people's priorities and values or to overcome challenges posed by certain natural settings. Indeed, one of the most essential qualities of folk architecture concerns its ecological character. That is, folk dwellings and structures are adapted to the local environment and usually reflect the natural characteristics of a place or region. On a global basis folk architecture is most commonly associated with rural or small town locations.

Numerous folk architectural traditions exist within the United States, echoing its diverse cultural composition. For purposes of manageability, two broad traditions can be identified in the United States. These are European-derived and American Indian derived. In many ways these two categories fail to capture full range of types and styles but provide a useful starting point nonetheless. European-derived folk architecture is emphasized here, but both traditions have shaped the character and development of Oklahoma's folk architecture, particularly its dwellings.

Of the settlement hearths established in colonial America, three contributed significantly to the emergence of distinctive regional differences in such things as agriculture, foodways, dialect, and folk architecture. The first of these hearths centered on the Chesapeake Bay and Tidewater region of Virginia and Maryland and contributed to the emergence of the region referred to as the Lower South or Tidewater South. The second hearth grew out of the Puritan settlement of the Massachusetts Bay Colony and played a part in the creation of the New England or northern region. The third developed in southeastern Pennsylvania and Delaware and was the starting point for the emergence of the Middle Atlantic or Midland region. The westward expansion of settlement gradually extended the domains of these regions beyond their initial hearths, carrying New England influences across the upper Midwest and Midland influences across the interior South. As a result, Oklahoma finds itself squarely within the Midland domain, although geographically it straddles the ecological boundary between the eastern woodlands and the western plains.

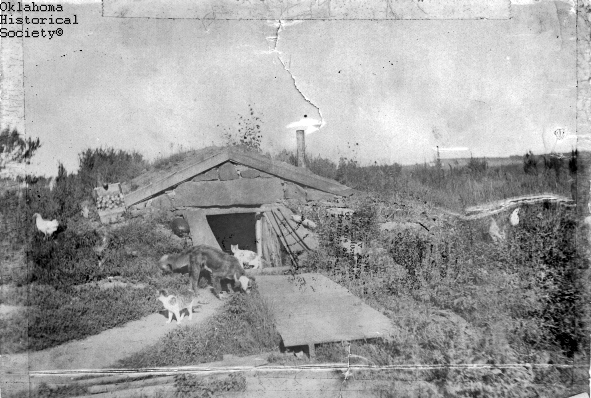

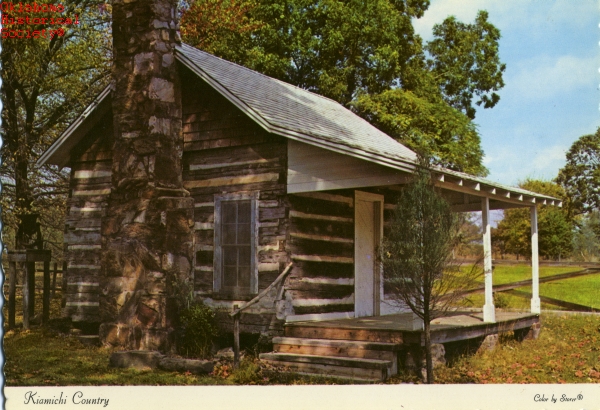

Midland folk architecture shares a number of identifying features. It is initially associated with notched log construction. By the latter part of the nineteenth century, however, wood-framing techniques had replaced log construction. Midland folk architecture also includes a modest number of distinctive floor plans. The basic building block of the Midland house is the Midland single pen, a one-room structure approximately eighteen feet on a side. Some scholars distinguish between log cabins and log houses. While both are single-pen dwellings, the former is a temporary and more rudimentary first-generation dwelling. Across the western half of Oklahoma the dugout was typically the first kind of single-pen dwelling. Most dugouts were eventually replaced by sod houses, which in turn were replaced by wood-frame houses.

Another slightly larger, one-room dwelling is the Midland hall-and-parlor house. A rectangular house, as its name suggests, its interior space is sometimes partitioned into two rooms. Both single-pen and hall-and-parlor houses occur with considerable frequency in Oklahoma.

Enlarging the single-pen house gave rise to several different kinds of gable-ended, two-room Midland structures or double-pen plans. Placing two pens side by side created a Midland type known as a Cumberland house, and placing the second pen such that the chimney was sandwiched between the two rooms created a saddlebag house. Gen. Douglas A. Cooper's home at Fort Washita may be the most visible saddlebag house in Oklahoma. If the two pens are detached, leaving an open space or breezeway between the two pens, the result is a dogtrot house. Dogtrot houses are known to have been a favored house type in Indian Territory well before the Civil War. Moreover, the Southeastern Indians had adopted notched log construction and built both single and double-pen dwellings in Indian Territory. Sequoyah's home near Sallisaw provides an example of an early-nineteenth-century single-pen log dwelling.

Double-pen houses could be enlarged by creating a second story, and the result was a Midland type known as an "I-house." I-houses are two-story houses that are two rooms wide but only one room deep. Thus, when viewed from the side, they appear unusually narrow. Both urban and rural examples of double-pen and I-houses exist in Oklahoma, but I-houses are less common here. One of the most notable examples of a dogtrot I-house in Oklahoma, and possibly one of the oldest, is the home of Chief Greenwood LeFlore near Swink in Choctaw County.

Although Oklahoma is situated within the Midland region, its folk architecture has been shaped by southern, and to a lesser extent, northern influences. Two southern house types diffused into Oklahoma and have become closely associated with the state's folk architecture: the shotgun house and the southern pyramidal. The distinguishing features of the southern pyramidal include a square floor plan with four rooms, sometimes a central hall, and a steeply pitched roof that rises to a pyramid or slightly truncated pyramid. The southern pyramidal may have one or two stories, and although it resembles the foursquare house, it possesses a very different developmental history.

See Also

ARCHITECTURE, FOLKLIFE, FOURSQUARE HOUSE, I-HOUSE, PYRAMIDAL HOUSE, SHOTGUN HOUSE