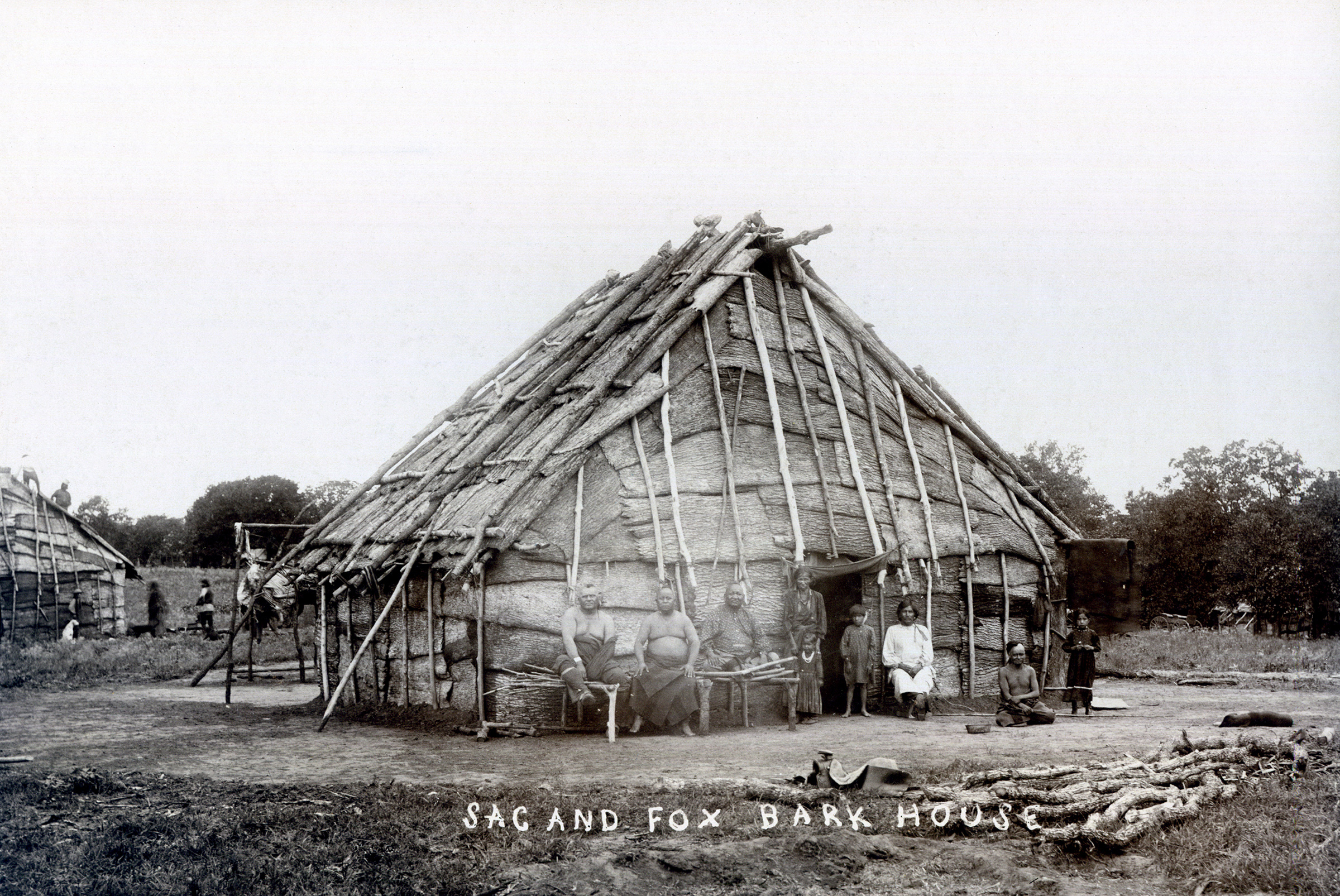

SAC AND FOX.

Federally recognized as the "Sac and Fox Tribe of Indians of the Mississippi River in Oklahoma," and commonly known as the Sac and Fox Nation, the Thakiwaki (Sauk/Sac) are an Algonquian people indigenous to the Western Great Lakes region. Through a series of dislocations they found themselves in the Indian Territory (now Oklahoma) in the 1870s. The misnomer "Sac and Fox" is a historical accident, a conflation of "Sac" (Sauk), or Thâkîwaki ("people coming forth [from the outlet]," i.e., "from the water"), and "Fox," or Meskwâki ("people of the red earth") misapplied by the U.S. government during treaty negotiations in 1804.

Although they were historically associated and closely related by language and culture, the two peoples have always remained geographically and politically distinct. The Meskwaki have resided on the Meskwaki Settlement in central Iowa since 1856, and the Thakiwaki have been in central Oklahoma since the 1870s. The contemporary Sac and Fox population in Oklahoma claim to be predominantly of Thakiwaki decent and typically refer to themselves as both "Sac and Fox" and Sauk, and to their heritage language as Sauk.

At the time of European contact the Thakiwaki resided in the Saginaw Valley near Saginaw Bay of Lake Huron and Green Bay of Lake Michigan on the east-central peninsula of what is now the state of Michigan. Saginaw is actually derived from the old Sauk term Sâkînâwe, "(in) Sauk country," and Chicago, an area once known for its plentiful wild onions, is derived from shekâkôhaki, a Sauk word meaning "onions" or "land of onions." Dislocated from their indigenous lands through a series of armed conflicts and treaties, the Sac and Fox resided for a time in Illinois (1764 to 1830), briefly in Iowa (1831 to 1846), and in Kansas (1847 to 1867), prior to being removed to the Indian Territory in the 1870s.

During their residence in present Illinois the Thakiwaki principally lived in a settlement near Rock Island, situated a short distance above the confluence of the Mississippi and Rock rivers. The settlement was known as the great town of Sâkînâke, the Saukenuk of history. The most notable armed conflict involving the Thakiwaki is perhaps the three-month Black Hawk War of 1832. That conflict occurred shortly after their removal, according to treaty agreement, from Saukenuk to Iowa. It entailed an extended series of skirmishes between United States infantrymen and a dissident band of one thousand that included five hundred warriors led by Black Hawk. Although Black Hawk survived, the event itself ended tragically with the slaughter of unarmed Thakiwaki crossing the Mississippi River. Afterward, only 150 to 200 of the original thousand dissidents rejoined their compliant counterparts on the Iowa side of the river.

Some Thakiwaki call the Black Hawk War a historical example of an enduring spirit of resistance. Indeed, Black Hawk's name and a symbolic representation occupy the center of the contemporary Sac & Fox Nation seal and flag. The war, however, has also been viewed as a watershed, signifying the last armed resistance to Euroamerican encroachment and resettlement east of the Mississippi River. A contemporary of Black Hawk, Keokuk provides an important contrast. An effective orator and diplomat, Keokuk desired to negotiate and maintain peaceful relations with what he perceived to be an ever growing and expanding Euroamerican population. These historical embodiments, one of resistance and autonomy and another of peace and diplomacy, represent a continuing dynamic in Thakiwaki political life.

Members of Thakiwaki society have historically belonged to one of two groups–shkasha or kîshkôha–as well as to a clan that has harbored both familial importance as a name group and ceremonial significance as a ritual unit. These memberships have served significant functions in the continued practice of cultural observances, including adoption, naming, and burial ceremonies, a seasonal cycle of clan feasts, and various dances. Members have also been involved in the religious practices of the Drum Society, the Native American Church, and Christianity. Important social events have included an annual powwow held in July on tribal grounds, numerous benefit and honor dances, veterans' events, banquets, holiday celebrations, and the occasional rodeo.

The best known Sac and Fox individual may be Olympian Jim Thorpe (1888–1953), symbolically represented on the Sac and Fox Nation seal and flag by five Olympic rings. Something that is perhaps much less known is the development in 1983 of the nation's own system for vehicle registration and issuance of license plates to Sac and Fox Nation members. Although the state of Oklahoma fought the practice, on May 17, 1993, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in favor of the Sac and Fox Nation. The Thakiwaki now call May 17 "Victory Day." Other American Indian nations have since followed their lead.

Originally governed by a hereditary clan system, the Sac and Fox Nation have a constitutional government and business committee. Leadership lies with an elected body of five officials: principal chief, second chief, secretary, treasurer, and committee member. Elections are held in August on odd-numbered years, and each official serves a four-year term. The national headquarters is located five miles south of Stroud and adjacent to U.S. Highway 377 and State Highway 99 and is situated on approximately 1,032 acres of the original 480,000-acre Sac and Fox Reservation (1867–91). Often called Thâkînâwe, "Sauk country," the former reservation area is the center of contemporary community life. Most of the approximately three thousand Sac and Fox Nation members live within or near the area, concentrated around the towns of Cushing to the north, Shawnee to the south, and Stroud in between.