SLAVERY.

In the 1830s African American slavery was established in the Indian Territory, the region that would become Oklahoma. By the late eighteenth century, when more than one-half million Africans were enslaved in the South, the five southern Indian societies of that region Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole had come to include both enslaved Blacks and small numbers of free African Americans. A few hundred Black slaves had run away from their white masters and sought refuge in Creek, Seminole, and Cherokee settlements, which received them as free people. While some Indian communities incorporated Black individuals as free people, American Indians in each of the nations, except the Seminole, began to purchase African Americans as slaves.

A number of Indian farmers had large tracts of land under cultivation and used enslaved laborers to produce cotton and surplus crops for sale and profit. Most Indian slave owners, however, practiced subsistence agriculture, and both slaves and masters labored side by side in the fields. By the 1830s more than three thousand African Americans, mostly enslaved, lived among the tribes.

American Indians brought their slaves to the west in the 1830s and 1840s when the federal government removed the nations from the southern states. The Cherokee, with more than fifteen hundred, had the largest number. Enslaved persons removed with the other nations ranged from approximately three hundred in the Creek Nation to more than twelve hundred in the Chickasaw Nation. When the Civil War erupted in 1861, more than eight thousand Black men and women were enslaved in Indian Territory. They comprised 14 percent of the population. Slavery continued in the territory through the Civil War, after which the five nations legally abolished the practice.

In Indian Territory both Blacks and Indians endured the harsh conditions, disease, and deprivation of removal. Black slaves performed much of the physical labor involved in removal. For example, they loaded wagons, cleared the roads, and led the teams of livestock along the way. When the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole people settled in their new homes, they reestablished their national governments and passed slave codes that protected owners' property rights in enslaved people and restricted slaves' rights.

Most slaves in Indian Territory were owned by wealthy and prominent men, many of whom wielded considerable political power. Their slaves worked primarily as agricultural laborers, cultivating both cotton for their master's profit and food for consumption. Some slaves were skilled laborers, such as seamstresses and blacksmiths. Indian slaveholders bought and sold slaves, often doing business with white slaveholders in the neighboring states of Texas and Arkansas. Similarities existed between slavery in the states and the Indian Territory. Enslaved people were considered property, and their labor was exploited for their masters' profit.

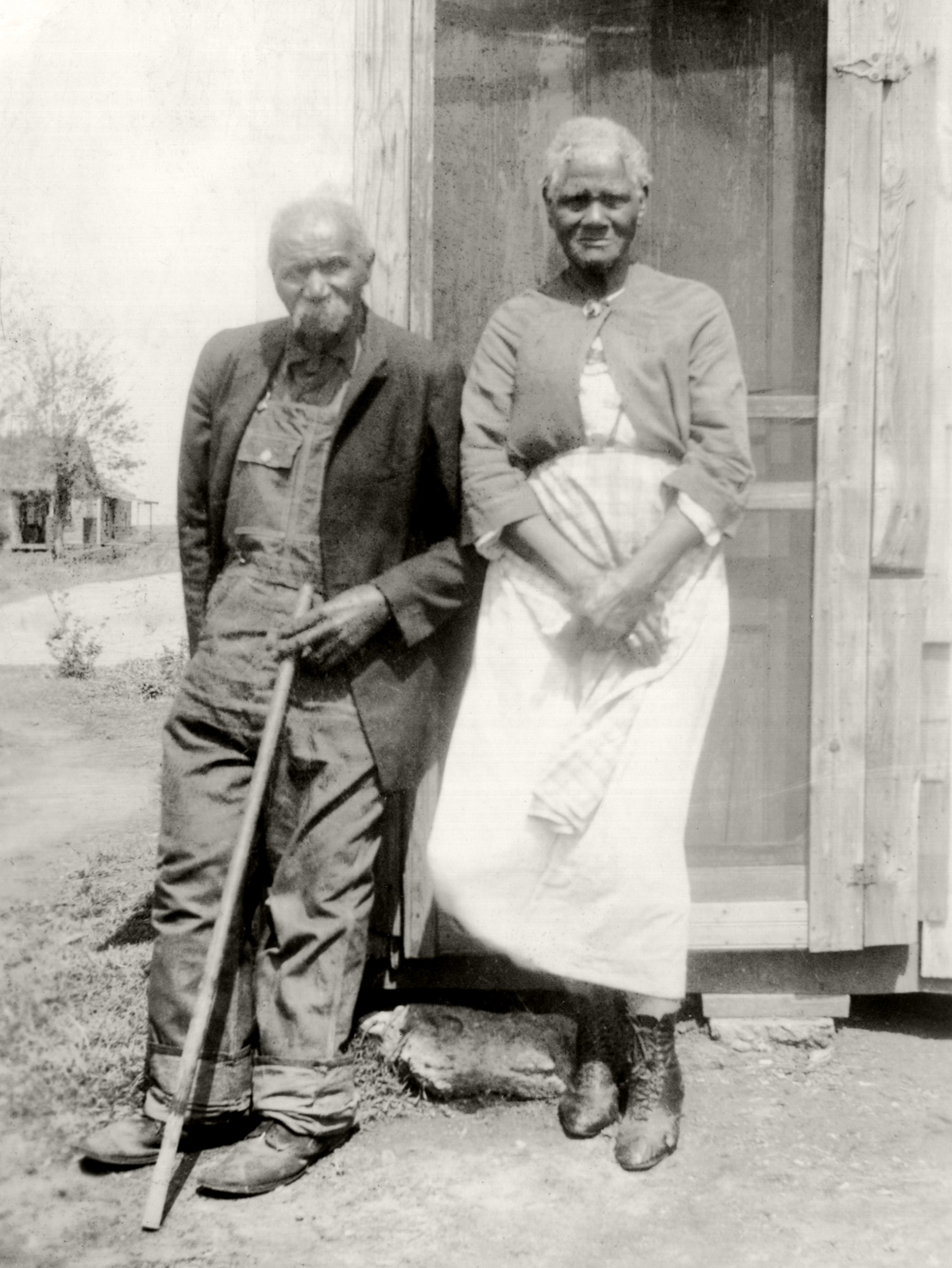

However, slavery in the Indian nations differed in significant ways from American slavery. By most accounts, Black families owned by Indians were not sold apart and usually were permitted to live together even if individual family members had different masters. Indian slaveholders generally did not use violence to control their slaves, and slaves were not regarded as dehumanized beasts of burden. Despite the nations' restrictive slave codes, Blacks were allowed to gather on their own for religious services and were usually permitted to learn to read and write. Slaves who spoke and wrote English, furthermore, provided important services as translators for those Indians who were not fluent in English. Because many slaves had been born and raised in the Indian nations and had long family histories among the Indians, they shared many of the distinctive features of Indian culture and daily life. Black women in the Creek Nation, for example, prepared food according Indian customs and wore the same style of clothing as Creek women.

Although enslaved persons did not have lives characterized by brutality and exploitation, they nonetheless occupied a degraded status as unfree people in the Indian nations, and their acts of resistance highlighted their desire to acquire freedom. In 1842 slaves in the Cherokee Nation took horses, supplies, guns, and ammunition and attempted to flee from the Indian Territory to Mexico, where slavery had been abolished. In 1850 Seminole leader Wild Cat left the Indian Territory with approximately three hundred Blacks to establish a settlement in Mexico.

The laws and customs governing slavery differed in each nation, but the Seminole had the most distinctive form of involuntary servitude. In Florida the Seminole had acquired from five hundred to one thousand slaves by harboring runaways from white and Creek masters and by seizing slaves from whites and Indians. Before and after removal from Florida Black slaves in the Seminole Nation were allowed to live and labor on their own, and they were obligated only to provide an annual tribute of food to their masters. Many historians refer to them as "maroons," meaning escaped slaves who lived in their own communities. Many Blacks, however, intermarried with Seminole, and some Black men acquired positions of leadership and authority in the nation. After removal both Indian and white slaveholders blamed the Seminole for encouraging and assisting runaway and rebellious slaves in Indian Territory.

In each of the southern Indian nations some people objected to the adoption of Anglo-American culture, including plantation slavery. Antislavery Indians, along with white missionaries in the nations, formed abolitionist factions, such as the Keetowahs in the Cherokee nation, which sought to end slavery and to restore traditional values and practices in the nations. Shortly after the outbreak of the Civil War pro-Confederate leaders in each of the nations entered treaties with the Confederacy in the summer of 1861.

After the Civil War ended, the United States negotiated new treaties with each of the five southern Indian nations. Ratified in 1866, the treaties provided for the abolition of slavery and the extension of citizenship, including land rights, to the freed slaves. Through the rest of the century, Blacks in the nations struggled to secure their citizenship and land rights. When the five nations were dissolved under the Curtis Act (1898), both Blacks and Indians were compelled to accept land allotments and become legal residents of the state of Oklahoma.

See Also

AFRICAN AMERICANS, ALL-BLACK TOWNS, CIVIL WAR ERA, FREEDMEN, INDIAN TERRITORY, SLAVE REVOLT OF 1842