The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture

AFRICAN AMERICANS.

The history of Black Oklahomans is linked closely to westward expansion and the desire for land in nineteenth-century America. During that period white farmers craved cotton lands in what is now the American southeast, and they pressured the government to remove Indian tribes from the region. Indians, the Five Tribes, had lived upon this land for many years, growing crops, raising families, and developing their own culture. In response to farmers' demands, however, the federal government began a systematic policy of Indian removal in the 1830s. Enslaved African Americans came with their Indian masters across the Trail of Tears to their new territorial home in the West, to what is now the state of Oklahoma.

Until its abolition after the Civil War era, enslavement became a fixture in Indian Territory, but historians continue to debate the nature of the institution among the Indians. Some argue that it hardly resembled the institution established in the Deep South, but was more akin to indentured servitude of early America. Others differ, contending that "bondage was bondage," and that enthrallment implied a kind of brutality that made it similar to the chattel slavery of the Old South. Whatever the argument, slaves attempted to escape their bondage by running away, and they also revolted against their Indian masters in other ways. In Indian Territory, as elsewhere, both white and Black abolitionists worked openly and clandestinely to overthrow slavery. After the Civil War the federal government granted freedom to Indians' slaves, and it forced the tribes to grant allotments of lands to Black persons. Although some Indians disliked that idea, most of the former slaves and free Black men and women among the tribes received some acreage.

As settlers sustained their demands for more soil, the federal government opened for settlement a section within Indian Territory in 1889 called the Unassigned Lands, an area of land in central Oklahoma not granted to any group of Indians. In the Land Run of 1889 whites and a few Black settlers descended upon the territory to stake out homesteads. The following year the U.S. Congress created Oklahoma Territory, roughly the western half of the present state.

The Black population of the two territories grew as boosters described them as a land of opportunity and freedom. Along with this growth went a movement for an All-Black state. Led by an energetic promoter and politician, Edward P. McCabe, founder of the town of Langston, the Black statehood effort never had much chance of success. The work of McCabe and other boosters, however, did lead to the establishment of more All-Black towns in the territories. Some Black towns had sprung up before the Civil War, but most came into being following that conflict. By some estimates, as many as fifty of these communities may have existed at one time in Oklahoma's history, far more than scholars once believed. Whatever the number, their significance resides in the determination of Black people to escape discrimination, to seek reinforcement for their racial ideas, and to acquire some control over their own lives. Severe economic difficulty took its toll on Black towns, and by the 1940s the majority of them had disappeared or were only small, unincorporated places. A few, such as Boley and Langston, still remained, but only as hopeful reminders of what may have happened had history taken a different course.

For a time, fluid social relationships existed between Black and white settlers in the territories, despite a history of enslavement in pre–Civil War Indian Territory. White migration from the Deep South and the increasing number of Blacks led to restrictive racial laws and customs. The growing economic success of Blacks in particular affected race relations. Black men energetically established banks and other businesses, and a sizeable portion of African Americans bought their own land to start farms. By the turn of the twentieth century, Black workers began to compete for jobs reserved for whites in the territories' cities. As historian Danney Goble has correctly observed, economic progress and Black population growth made physical separation more difficult, if not impossible. Black advances challenged stereotypical attitudes toward race, and as a result, a new social arrangement soon appeared.

National developments also played an important role in altering race relations between Blacks and whites in the territories. The latter part of the nineteenth century witnessed a growth in white race consciousness that led to racial discrimination. In 1896 the U.S. Supreme Court issued its "separate but equal" doctrine in the Plessy v. Ferguson case that helped to enshrine Jim Crow into law for more than a half century. That decision removed any doubt from the minds of whites who wanted to limit the rights of Black individuals, especially in education. In the early stages of Oklahoma Territory, separate schools for Blacks and whites was optional, but in the late 1890s the territorial legislature passed statutes that effectively kept Black and white children apart. Faced with the reality of white attitudes toward separation, Black parents called for support of Black educational institutions for their children, including the establishment the Colored Agricultural and Normal University at Langston in 1897.

By the time delegates met in the Oklahoma Constitutional Convention at Guthrie in 1906 to organize a new state, both law and social customs had created an atmosphere for a completely segregated society. The battle over the place of Blacks in the newly proposed state of Oklahoma became a heated issue during the selection of representatives to the convention. The Democratic Party promised to separate the races, and with that as a central part of its platform, it ultimately secured an overwhelming majority of the delegates at Guthrie. Led by the Negro Press Association, Blacks waged a determined battle to defeat the forces of segregation but could not overcome the prosouthern sentiment that had taken root in the territories. The politicians at the convention wanted to redeem the commitment to keep the races apart in all areas of social life, but Republican Pres. Theodore Roosevelt had threatened to veto Oklahoma statehood if that took place. The spirit of the constitutional convention echoed in the racial language of its leader, William "Alfalfa Bill" Murray, who exclaimed that Blacks would always remain bootblacks, barbers, and farmers. The future governor of Oklahoma believed that African Americans would never rise to the equal of whites in the professions or become informed citizens capable of grappling with serious public questions.

Despite Roosevelt's threat, the delegates at Guthrie included a section in the Oklahoma Constitution that required separate schools. Yet they stopped short of the total legal segregation that white citizens desired. Higher education in Oklahoma would stay separate until the 1940s, and public schools in the state until 1955. Although Murray and his colleagues had not mandated full separation of the races, representatives to Oklahoma's First Legislature moved quickly to finish what the founding fathers had left undone. They passed a statute that separated Blacks and whites in public accommodations, and they approved a bill that gave enforcement power to the constitutional provision for segregated schools.

Disfranchisement of Blacks also stood high on Oklahoma's legislative agenda. Black voters had not been fooled by the politicians at Guthrie who wrote into the constitution that the state "shall never enact any law restricting the right of suffrage on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude." Democrats who controlled politics in Oklahoma drew little comfort from the lingering strength of the Republicans and Black allegiance to that party. The election of a Black man, A. C. Hamlin of Guthrie, to the First Legislature also made an impact upon those persons anxious to rid Blacks from state politics. Here, then, were incentives for white Democrats to remove the ballot from Black hands.

The law passed by the state legislature and ratified by the people in 1910 to disfranchise Black voters was the so-called "grandfather clause." This measure stipulated that potential voters must take and pass an examination that demonstrated an ability to read and write. However, it exempted descendants of citizens eligible to vote on January 1, 1866, a provision that adversely affected Blacks but favored whites as most of them met that requirement. For nearly five years the grandfather clause remained virtually intact until the U.S. Supreme Court declared it unconstitutional in the 1915 Guinn v. United States case. Nevertheless, a subsequent measure passed the legislature and limited Black voting; this law would remain on the books until it met with Court disapproval in 1939. The unrestricted right to the ballot, however, did not come to all Black Oklahomans until the Civil Rights era of the 1960s.

For nearly half a century the Jim Crow code established by the state of Oklahoma and its localities touched practically every facet of life that involved contact between the races, or the exercise of political and social relationships. Blacks experienced some of the worst discrimination in the area of economic opportunity. Although the Oklahoma Constitution and local ordinances did not prescribe low-paying, menial jobs for Black workers, custom and community attitudes proved as limiting as law itself. Clearly, whites realized the position they wanted Blacks to occupy within the economy. The difference in ways of making a living between Black and white Oklahomans measured the distance between them in a number of areas: education, health, housing, recreation, and other facets of life.

Tensions between Blacks and whites in Oklahoma occasionally led to outright racial violence. Violation of the Jim Crow rules or the unwritten etiquette of race relations could put Black persons at considerable risk. Although many white Oklahomans defended segregation as a means of ensuring racial peace, it encouraged random lawlessness and lynching or provided a defense for actions against Black individuals. During the territorial period racial intolerance had led to attacks against Blacks, and the beginning of the twentieth century saw an increase in the brutality against them. The irrational belief by whites of possible Black domination in the state, fear of economic competition, and efforts to silence Blacks politically, helped to foster an atmosphere for violence.

The most notorious act of racial conflict in Oklahoma history took place in Tulsa in 1921. Significantly, the violence in the state was part of a broader story of national intolerance that followed World War I. Yet the Tulsa violence represented a defining moment in Oklahoma's history, for it forecast the extent to which some white citizens would travel to achieve the ultimate subjugation of Black citizens. Much like the other riots of the period, the Tulsa disaster developed from a number of immediate and remote causes, among them irresponsible journalism, rumor, racial fears, tensions related to urban migration, and weak law enforcement. Although historians cannot specifically indict the Ku Klux Klan in starting the fight, the organization created a spirit of lawlessness that made it easier for some citizens to engage in mob activity.

A chance encounter by two people who had never met each other led to the Tulsa race massacre. When a young white woman, Sarah Page, accused Dick Rowland of making advances toward her in a downtown Tulsa elevator, she set the stage for the most disastrous racial episode in Oklahoma. Rowland's flight from the scene and his subsequent arrest by Tulsa authorities confirmed his guilt in the minds of citizens who believed that white womanhood must be protected at all cost. False newspaper reporting of the incident, describing Page as an orphan whose dress had been torn by the Black man, inflamed Tulsans and stoked the embers of racial hate. When Black men heard of plans to lynch young Rowland, they went to the jail in downtown Tulsa to protect him, but instead they confronted a group of white men determined to drive them back to their section of the city. The whites achieved their objective and then proceeded to burn down a large part of North Tulsa, where the majority of Blacks in the city resided. Gov. J. B. A. Robertson called out the National Guard to help police Tulsa, but by that time many homes and businesses, including the ones along Greenwood Avenue (Black Wall Street) had been destroyed by fire, with the loss of dozens of lives. Scholars may never know how many people perished in the tragic events of 1921, for it was difficult to account for those who were burned to death, buried in secret graves, or dumped in the river. Even a special study of the massacre eighty years later could not determine the number of persons who lost their lives.

The Tulsa violence did not alter racial policies in Tulsa or the state of Oklahoma. Tulsa remained unrepentant. Many whites laid blame on the aggressiveness of Black agitators for social equality or on militant Black groups from outside the state. A grand jury placed responsibility for the conflict squarely upon the shoulders of the Black men who went downtown to protect Rowland. At the opening of the twenty-first century, the Tulsa disaster continued to engender heated discussion. Oklahoma officially apologized for the tragic event, and in 2001 a Tulsa Race Riot Commission, established by the state legislature, called for reparations for victims of the violence.

Between the 1920s and the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s, two pervasive themes appear in African American history in Oklahoma: legal action against Jim Crow, especially in education, and Black community building. What seems remarkable in retrospect is the intensity with which Blacks sustained their assault upon segregation, violence, and intimidation. Black newspapers in Oklahoma played a key role in this effort, bitterly attacking racially conservative politicians who wanted to stifle Black progress. The most crusading pro-rights journals were found in the larger cities of Tulsa, Oklahoma City, and Muskogee. Although the newspapers had several notable Black editors, none made as great an impact on the state as Roscoe Dunjee of the Oklahoma City Black Dispatch. For more than fifty years Dunjee followed practically every development within the Black community in Oklahoma. A staunch believer in social reform, Dunjee guided the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in Oklahoma to much of its success.

Changing the racial system in Oklahoma was no easy task for Dunjee and other Black leaders, but their unrelenting efforts began to pay dividends in the period after World War II. Previous judicial challenges to segregation had brought few changes in Black life, especially in education. A significant victory in that field, however, came in the 1948 Sipuel v. Board of Regents of the University of Oklahoma case. Supported by Dunjee and represented by attorney Amos Hall of Tulsa, Ada Lois Sipuel applied for admission to the University of Oklahoma College of Law but was denied entrance. Upon appeal, the U.S. Supreme Court ordered Oklahoma to admit the Chickasha native. About the same time, another Black student, George McLaurin, entered the university at Norman, and when the institution segregated him from white students, the Court ruled in 1950 in McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents that the university had to treat him the same as white students. For all practical purposes, the Sipuel and McLaurin cases destroyed the legal foundation for segregation in higher education in the state of Oklahoma.

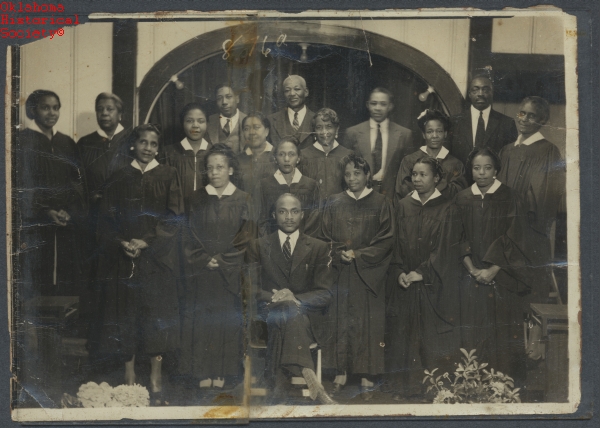

The struggle for equality has been a central motif in the history of Black Oklahomans, but the experience of African Americans in the state has transcended racial protest. Behind the walls of segregation existed a vigorous social, cultural, and institutional life. Preeminently, the Black church stood at the very center of Black community life. It represented not only a place to worship, but a valuable social outlet in an era when Oklahoma limited Black access to publicly supported facilities. Although Baptists and Methodists accounted for the overwhelming number of Black worshipers, a small number of other religious groups appeared in the community. By the mid-twentieth century, roughly eighty thousand Blacks had membership in the nearly eight hundred churches that dotted the Oklahoma landscape. Some scholars have viewed the African American church as religiously orthodox, but the state of Oklahoma had a number of ministers, such as E. W. Perry of Oklahoma City, who preached the social gospel and who taught that Christianity should reject injustice.

Oklahoma's Black residents established other social outlets and institutions designed to achieve some reasonable control over their own lives. Fraternal groups such as the Prince Hall Masons had come into existence before statehood. Women's clubs also appeared within the community, sponsored social activities for both young and old, and fought for stronger community institutions. The Oklahoma State Federation of Colored Women's Clubs, organized shortly after statehood, worked successfully with other groups for a school for delinquent boys at Boley and for a Black girls' facility at Taft. Also forming reading and recreational groups within the larger towns of Oklahoma, women were in the forefront in the battle for library facilities in cities such as Tulsa and Oklahoma City. Black Masons and their women's auxiliary group, the Eastern Star, supported citizenship programs and educational advancement through college scholarships. The Black community depended heavily on the church and community groups to provide a kind of safe haven from the harshness of racial discrimination. Through their own individual and collective efforts, Blacks achieved agency through the development of their own institutions. Even after the disappearance of segregation, many of these historic groups continued to thrive in the Black community.

The vibrancy of a strong Black culture, however, could not completely overcome the negative effects of an unequal society. Only law could do that. The 1954 U. S. Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, destroyed segregation in education, but perhaps more importantly, it knocked the props from under the social principle that had sustained Jim Crow. Oklahoma readily complied with the decision, and unlike some other places, no major violence took place in the state. Much of Oklahoma's success resulted from the bold leadership of its governor, Raymond Gary, a native of Little Dixie, the southern part of Oklahoma. In 1955 Oklahoma voters approved a constitutional provision, the Better Schools Amendment that effectively spelled the legal end to segregated schools in the state. Although some pockets of re-segregation reappeared in later years after an experiment with busing, a rebirth of the principle of legalized segregation never seemed likely in Oklahoma.

Sweeping changes took place in Oklahoma and the nation during the period that followed the Brown decision, the 1955 Montgomery, Alabama, bus boycott, and the emergence of Martin Luther King, Jr., as a national leader. Infused with King's teachings of nonviolent resistance, a dynamic Oklahoma City Black woman, Clara Luper, led the children of the NAACP Youth Council against segregated eating establishments in the city. Luper and her young army achieved some success with a "sit-in" movement that began in 1958, almost two years before the more celebrated one in Greensboro, North Carolina. Their efforts focused sharp attention upon segregation in public businesses and other establishments and brought some hard-won victories. Ultimately, however, total victory for equal treatment in public accommodations had to await the passage by Congress of the historic Civil Rights Act of 1964. Black Oklahomans took pride in the role they played in making that measure a reality, and for the support they gave to the successful Voting Rights Act a year later. Oklahoma heard the rhetoric and felt the impact of the so-called "Black Power" movement of the mid-1960s, but in its more militant form Black Power never acquired a firm grip on the state. In Oklahoma the movement revitalized interest in racial pride and a stronger Black demand for a truly just and integrated society.

Black people strongly emphasized Black cultural achievements during the era of civil rights. The teaching of Black history witnessed a rebirth in African American institutions and made its appearance in many predominantly white schools. Along with the movement went integration of faculties and staffs at white colleges and universities. Black intellectuals pointed proudly to the accomplishments of a long list of Black Oklahomans in important areas of American life, including John Hope Franklin in history, Melvin Tolson in poetry, Ralph Ellison in literature, Earl Grant, Jimmy Rushing, and Charlie Christian in popular music, and Leona Mitchell in opera. The establishment of museums, special exhibits, and archives that emphasized black achievement proliferated as interest grew between both Black and white Oklahomans.

Black political life quickened as the barriers to voting and office holding fell. Prior to the Civil Rights movement, only three Black politicians had served in legislative positions in Oklahoma: Green I. Currin and David J. Wallace during the territorial period, and A. C. Hamlin shortly after statehood. Following passage of the Voting Rights Act and congressional reapportionment in Oklahoma in the 1960s, Black representatives made their reappearance in the Oklahoma Legislature. The largest number of African Americans to serve in the state legislature at any given time over the years has been five. All have been aligned with the Democratic Party, and all have come from Tulsa or Oklahoma City. In 1994 Oklahoma elected its first Black congressman, Republican J. C. Watts, a former star quarterback for the University of Oklahoma Sooners football team. At the state and local level, more than one hundred Black men and women had served in elected positions throughout Oklahoma at the end of the twentieth century.

As they faced a new century, the Black Oklahoma community and their political representatives turned their attention to a broad set of problems that continued to hamper racial progress. They were aware that a gap still existed between the economic status of Black and white Oklahomans. Not surprisingly, then, Black legislators worked to support Black business and to promote affirmative measures that gave opportunity to persons once denied economic opportunity. They also addressed issues such as hate crimes, flying of the Confederate flag at the state capitol, the appointment of judges, better health care, greater access to education, support for Langston University, and the appointment of a commission to study the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921. As much as any generation before them, Black Oklahomans and their leaders believed that there was reason for hope in a new century and that they could overcome the crippling legacies of the past.

At the close of the twentieth century Oklahoma's 180,000 Black citizens could look back at a history that had gone from enslavement to freedom. Through their own institutional and community structures they became powerful agents for change. Indeed, few states in America made such a large impact upon the achievement of Black freedom as Oklahoma. It initiated and won significant civil rights cases in the U.S. Supreme Court, and it successfully employed nonviolent direct action, the sit-in, to destroy restrictive racial barriers. The changes that took place in this evolving democratic process did not quickly erase injustices created by a segregated past, but advances did come.

By the beginning of the twenty-first century most Oklahomans accepted the constitutional principle of equality, even though they may have disagreed about specific means to achieve that goal. They were certain, however, that the state and the country had traveled too far to turn back. Armed with a revitalized pride in their culture and hope for the future, Black Oklahomans exalted the best in their past and paid homage to a proud heritage that spoke of trials and triumph. Yet, like other citizens of their state, they had a sense of a broader history in common with other groups that made them genuine Sooners.

See Also

BUFFALO SOLDIERS, CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT, COLLEGES–AFRICAN AMERICAN, FRATERNAL ORDERS–AFRICAN AMERICAN, FREEDMEN, JUNETEENTH, LYNCHING, NAACP, NEWSPAPERS–AFRICAN AMERICAN, SEGREGATION, SENATE BILL ONE, SLAVERY, TULSA RACE MASSACRE

Learn More

William Bittle and Gilbert Geis, The Longest Way Home: Chief Alfred Sam's Back-to-Africa Movement (Detroit, Mich.: Wayne State University Press, 1964).

Norman Crockett, The Black Towns (Lawrence: Regents Press of Kansas, 1979).

George L. Cross, Blacks in White Colleges: Oklahoma's Landmark Cases (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1975).

Scott Ellsworth, Death in a Promised Land: The Tulsa Race Riot of 1921 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1982).

Ralph Ellison, Going to the Territory (New York: Random House, 1986).

Ada Lois Fisher, with Danney Goble, A Matter of Black and White: The Autobiography of Ada Lois Sipuel Fisher (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1996).

Jimmie Lewis Franklin, The Blacks in Oklahoma (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1980).

Jimmie Lewis Franklin, Journey Toward Hope: A History of Blacks in Oklahoma (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1982).

John Hope Franklin and John Whittington Franklin, eds., My Life and an Era: The Autobiography of Buck Colbert Franklin (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1997).

Rudi Halliburton, Red Over Black: Black Slavery Among the Cherokee Indians (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1977).

Clara Luper, Behold the Walls (Oklahoma City, Okla.: J. Wire, 1979).

Zella J. Black Patterson, Langston University: A History (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1979).

Kaye M. Teall, Black History in Oklahoma: A Resource Book (Oklahoma City, Okla.: Oklahoma City Public Schools, 1971).

Murray R. Wickett, Contested Territory: Native Americans and African Americans in Oklahoma, 1865–1907 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2000).

Related Resources

Citation

The following (as per The Chicago Manual of Style, 17th edition) is the preferred citation for articles:

Jimmie Lewis Franklin, “African Americans,” The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry?entry=AF003.

Published January 15, 2010

Last updated July 24, 2024

© Oklahoma Historical Society