The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture

CHEYENNE, SOUTHERN.

The Cheyenne people carry a tribal name received from their Siouian allies when they all lived in present Minnesota in the 1500s. The name means "foreign speakers" and was used by the Sioux in reference to Algonquian-speaking tribes. The Cheyenne, however, refer to themselves by the name "Tsistsistas," an old term whose meaning is uncertain. This name did not appear in print until the late 1800s and is not generally used by non-Cheyenne, both because the term "Cheyenne" is imbedded in American historical documents and because many English-speakers find "Tsistsistas" difficult to pronounce. The term is preferred, however, by those who speak the Cheyenne language and adhere to the traditional culture. About eight hundred Cheyenne in Oklahoma still speak their native tongue.

From Minnesota, Cheyenne bands, who then lacked horses, migrated westward in the 1700s, developing alli-ances with the Lakota, or Teton Sioux, and preceded the Teton across the Mississippi River into present North and South Dakota. Although the Cheyenne had been hunters and gatherers in Minnesota, some bands during their migration built villages and grew corn along the rivers of the Plains. The best-known site is Biesterfeldt, near Lisbon, North Dakota. Other bands acquired horses and adopted buffalo hunting, helping invent the tipi-dwelling, nomadic way of life known to students of American Indians. During that time diverse Cheyenne bands lived east of the Black Hills of South Dakota, and it was there that the prophet Sweet Medicine entered a cave in the mountain called Nowahwus, known to English-speakers as Bear Butte, and received the four sacred arrows that are still revered by the tribe.

Sweet Medicine organized the military societies, led by war chiefs, whose duties were to keep order and to maintain a hunting territory. Sweet Medicine also established a judicial system, operated by forty-four senior men known as peace chiefs. Most importantly, Sweet Medicine forbade the killing of one Cheyenne by another, an act that required the cleansing of the sacred arrows in a special ceremony. Sweet Medicine thus created the Cheyenne Nation, sovereign and independent.

Over the next century the Cheyenne established a hunting territory between the forks of the Platte River in Nebraska, Wyoming, and Colorado and formed an alliance with the Arapaho, who lived nearer the Rocky Mountains. Although the Cheyenne and the Arapaho were both small nations, with about three thousand persons each, as a combined military force they were formidable. They drove the Kiowa south and prevented the Shoshone from entering the Great Plains from the west. The Cheyenne and Arapaho kept the Blackfeet and the Pawnee out of their hunting territory and became the dominant traders in guns, horses, and buffalo skins in the central plains. At its greatest extent Cheyenne territory stretched from Montana to Texas and included the Oklahoma Panhandle and the areas around the Cimarron and Washita rivers in western Oklahoma.

At the close of the Civil War in 1865 the Cheyenne faced their most formidable enemies, the encroaching Americans. By that time, immigrant traffic had denuded the landscape along the Oregon and Santa Fe trails, splitting the Cheyenne into a northern group, destined for a Montana reservation, and the Southern Cheyenne, who, with their Southern Arapaho allies, ended up in Oklahoma. The period from 1830 to 1870 was generally characterized by a series of treaties with the U.S. government, punctuated by episodes of warfare. For the Cheyenne, military high points were their defeat of U.S. Army forces near Fort Kearny in 1866 and at Beecher Island in 1868 and their victory over Gen. George Armstrong Custer's troops at the Battle of the Little Big Horn in 1876. The low points were their losses at Summit Springs, Colorado, in 1869 and at the Battle of the Washita in 1868 and the massacre of about two hundred noncombatants by U.S. forces at Sand Creek, Colorado, in 1864.

After 1869 Southern Cheyenne bands and families assembled on their assigned reservation in Indian Territory. Fort Reno housed the soldiers who guarded them, and the town of El Reno grew up as a service center for the reservation and the fort. In selecting land to constitute a three-and-one-half million-acre reservation, government officials operated by administrative order, ignoring the numerous treaties signed by the Cheyenne.

Initially, Cheyenne bands gathered around government facilities at Darlington, near Fort Reno, and at Cantonment, near present Canton, where they received rations. After a scandal involving leasing of lands to non-Indian cattlemen, the bands were allowed to disperse around the reservation. Their camping grounds later became the sites of such towns as Hammon, Clinton, Thomas, Seiling, Longdale, Watonga, Calumet, and Kingfisher. With the help of Quaker missionaries, the Cheyenne began to prosper from farming until the Dawes Act (General Allotment Act) of 1887 required them to surrender three million acres of their reservation and settle on 80-acre and 160-acre allotments. Not wanting to live on dispersed plots of land, many Cheyenne leased their allotments to non-Indians and worked in agriculture or manufacturing. Employment was also increasingly available in the tribal government and government-sponsored projects. Since World War II many young and middle-aged Cheyenne have migrated to cities to work, especially to Oklahoma City, Dallas, and Los Angeles.

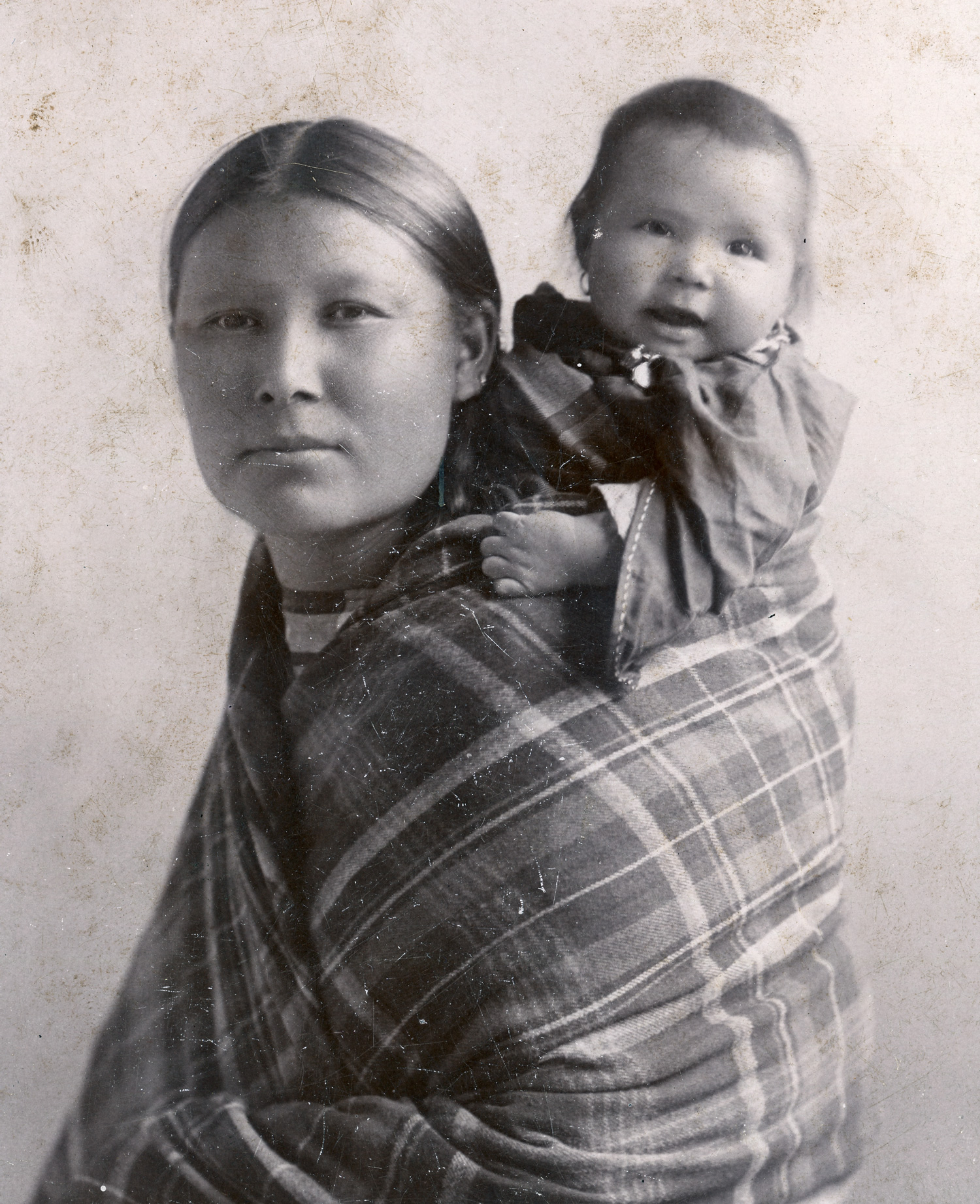

For Cheyenne people the extended family remains the most important social unit, consisting of grandparents and their children and grandchildren, perhaps twenty or thirty people in all. These families frequently live in adjacent houses in the towns of western Oklahoma or in a cluster of houses in more remote rural areas. Family members see each other often and share economic resources. At the town level, there are gourd dance and veterans' groups, women's craft groups, peyote groups, and Indian Christian churches, all of which unite the local Cheyenne community across family boundaries. These groups support dinners, dances, and powwows. The annual performance of their Arrow Renewal and Sun Dance ceremonies is a source of pride for the Southern Cheyenne, symbolizing their survival and their hope for the future. Visitors attend the ceremonies by invitation only. Unlike powwows, these are not public or commercial events.

The traditional laws governing Cheyenne people are supplemented by the oral traditions of chiefs and religious leaders. This central body of legal authority is the subject of The Cheyenne Way, by Karl Llewellyn and E. Adamson Hoebel. A separate body of "Indian law" is being built by the operation of a federally sponsored Indian court system, and although all Indian people are subject to federal laws, there are some areas of sensitivity and dispute between Cheyenne people and state and local authorities. Patches of federally administered "trust land" survive in the reservation area where the state, counties, and cities may not have complete authority. Especially at issue are the right of arrest, child custody, and questions surrounding traditional religious practices. All of these remain under negotiation by federal, state, local, and tribal authorities.

The Cheyennes and Arapahos share a tribal government, with equal representation of four members each on a business committee headquartered at Concho, near El Reno. The committee oversees four smoke shops where tax-reduced tobacco products are sold, the Lucky Star Casino at Concho, a bingo hall at Watonga, a recreation complex at Cantonment Lake, and a three-thousand-acre farming and ranching operation. Federal government welfare programs are funneled through the tribal government for the benefit of children, elders, and the disabled. The tribe also administers education projects, but there is no longer an "Indian school" on the reservation. Federal schooling off the reservation is available for qualified students, but almost all Cheyenne children attend the same local schools as non-Indians. Only about eighty thousand acres of the former reservation remain in Indian hands. Ten thousand acres of trust land are owned by the tribal government and seventy thousand acres by individuals. Some income is derived from oil and gas royalties, and rent is received from leasing trust land for grazing.

There were 11,507 enrolled Cheyenne-Arapaho citizens in 2003. Of those, about eight thousand would consider themselves Cheyenne. There have been attempts to separate Southern Cheyenne from Southern Arapaho administratively, but with continued intermarriage such efforts become more difficult. A current issue concerning many Cheyenne and Arapaho is the receipt of indemnities for the Sand Creek Massacre. Although the federal government promised compensation in 1865, no payment has been made.

See Also

AMERICAN INDIANS, ARAPAHO–SOUTHERN, RANCHING–AMERICAN INDIAN, TERMINATION AND RELOCATION PROGRAMS