DANCE HALLS.

In the late nineteenth century dance halls provided a public space where young people could mingle with their peers and escape restrictions placed on them by parents. There, also, employed men and women found a relaxing refuge after work. A dance hall has been defined as a place that is open to the public and in which a fee can be charged for the privilege of dancing.

Dance halls first appeared in Oklahoma Territory soon after the Land Run of 1889 and flourished after statehood. The Euclid and Dreamland were two of the first such establishments to open in Oklahoma City. By 1919 the Hispanic population frequented a dance hall at Pine and Harvey avenues. By the 1930s jazz and blues music drifted from the third floor of the African American venue known as Slaughter's Hall in the Deep Deuce district on Northeast Second Street in Oklahoma City. Through the years Cain's Ballroom in Tulsa has been home to country music and Western swing made popular by Bob Wills and his Texas Playboys. In Tulsa's Greenwood District, African Americans patronized The Rhythm Club, Casa Dell, Rialto Theater, and The Hole. Following a national trend, in the early twentieth century Oklahomans opened amusement parks in large urban centers. Some of these offered dance pavilions such as those at Delmar Garden and Belle Isle Park in Oklahoma City and at Casa Loma in Crystal City Amusement Park near Tulsa.

Small towns also offered opportunities for socializing and dancing. In the 1920s oil-field workers enjoyed the dance halls in the boomtowns of Cromwell, Earlsboro, and Seminole. Earlsboro offered the Green Lantern, Thompson's, and the Forty-Niner. Cromwell boasted Jones', Ma Murphy's, and Roy Kroker's, places in which dances cost fifteen cents. In July 1927 the town of Seminole reported that it had a shortage of girls and had to "import" them from larger urban areas such as Tulsa.

An establishment in which a customer paid a fee to dance with a hostess was known as a "taxi-dance" hall. In Seminole a two-minute dance cost a quarter (ten cents to the proprietor, ten cents to the girl, and five cents to the musicians). In Bodine City (southeast of Oklahoma City) a tin shack served as Curley Saxton's dance hall. Three African Americans furnished music, and a five-minute dance cost fifteen cents (the proprietor, the girl, and the musicians received equal shares).

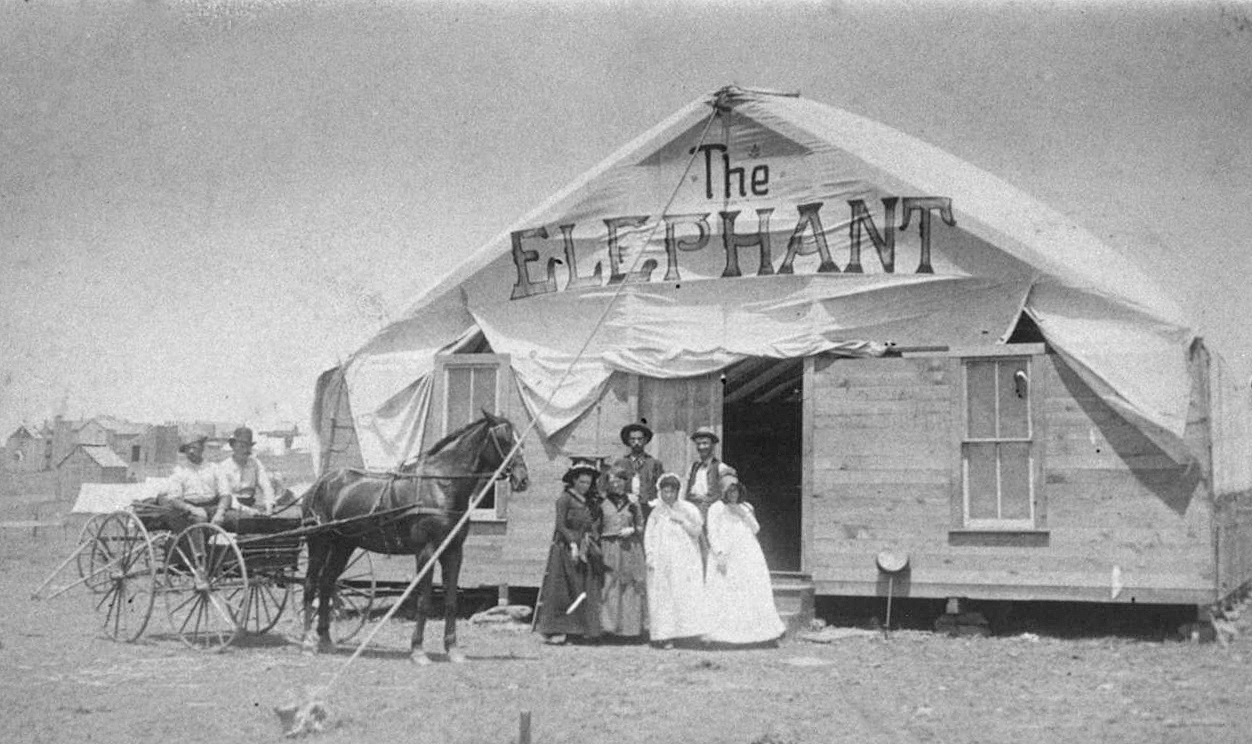

It is generally believed the word "honky-tonk," meaning a bar with a dance floor and stage for musicians, first appeared in print in 1894 in the Daily Ardmoreite (Ardmore, Oklahoma). A jazz orchestra played at Murphy's, and nickelodeons provided dance music for patrons of the "choc" beer joints or honky-tonks in Krebs, located in Oklahoma's coal-mining district. The former town of Beer City in Texas County, Oklahoma, received its name due to the number of dance halls and saloons that sold beer and whiskey.

Businesses that provided food and drink and that were located outside the city limits were called "roadhouses," and also honky-tonks, by Southern whites. Not regulated by city ordinances, roadhouses catered to individuals with automobiles and lured a less-than-desirable clientele. At the Country Inn, outside Oklahoma City, guests who desired to dance paid a quarter to operate an electric piano. The Riverside Inn, located at the west end of Reno Avenue in Oklahoma City, allowed dancing on Sundays, and whiskey could be obtained from a bootlegger at a nearby building.

Ethnic groups, fraternal organizations, and individual social clubs also built dance halls for their members. For example, in 1901 the Czechs living in Yukon, Oklahoma, established the Czech Hall. In Oklahoma City the Dania Scandinavia restaurant received a dance hall permit in 1938. Folk music such as the polka and schottische would have been provided to dancing couples at these establishments.

During the Progressive Era reformists worked to pass city ordinances placing restrictions on dance halls. The 1913 Oklahoma City ordinance required that these establishments close at 11:30 p.m. and on Sundays. Only individuals over the age of eighteen were admitted, and it was unlawful to drink liquor or engage in any "vulgar" dances. Tulsa passed a similar ordinance in August 1917. Society's concern about dancing, and dancing in public, resulted from the popularity of the "animal" dances known as the bunny hug, the grizzly bear, and the fox trot, which had been created during the early 1900s.

In an article published in the Journal of Popular Culture in 1973, social historian Russel B. Nye stated that the popularity of public dancing in the United States peaked between 1920 and 1940. World War II disrupted this form of recreation, and the advent of television, drive-in movies, and discotheques in the 1950s and 1960s changed Americans' leisure habits. Although the number of dance halls had declined by the turn of the twenty-first century, couples continued to "boot-scoot" across the dance floors of Graham Central Station in Oklahoma City, the Tumbleweed in Stillwater, and the Caravan Cattle Company in Tulsa.