The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture

LAND RUNS, WOMEN IN.

African American as well as white women participated in the Oklahoma land runs for various reasons. Like men, they were enticed by the glowing reports, the built-up excitement, the novelty of a land run, and the availability of land. Married women usually followed in their husbands' footsteps after the decision was made that the family was moving to the "Land of the Fair God." Single and widowed women came for the adventure or to better themselves financially, because, as provided by the Homestead Act, single women over the age of twenty-one and head of a household could claim a 160-acre homestead. Young and old, they came with their most cherished possessions by wagon and horseback. The more fortunate homesteader made the run by train, and the less fortunate entered the race on foot.

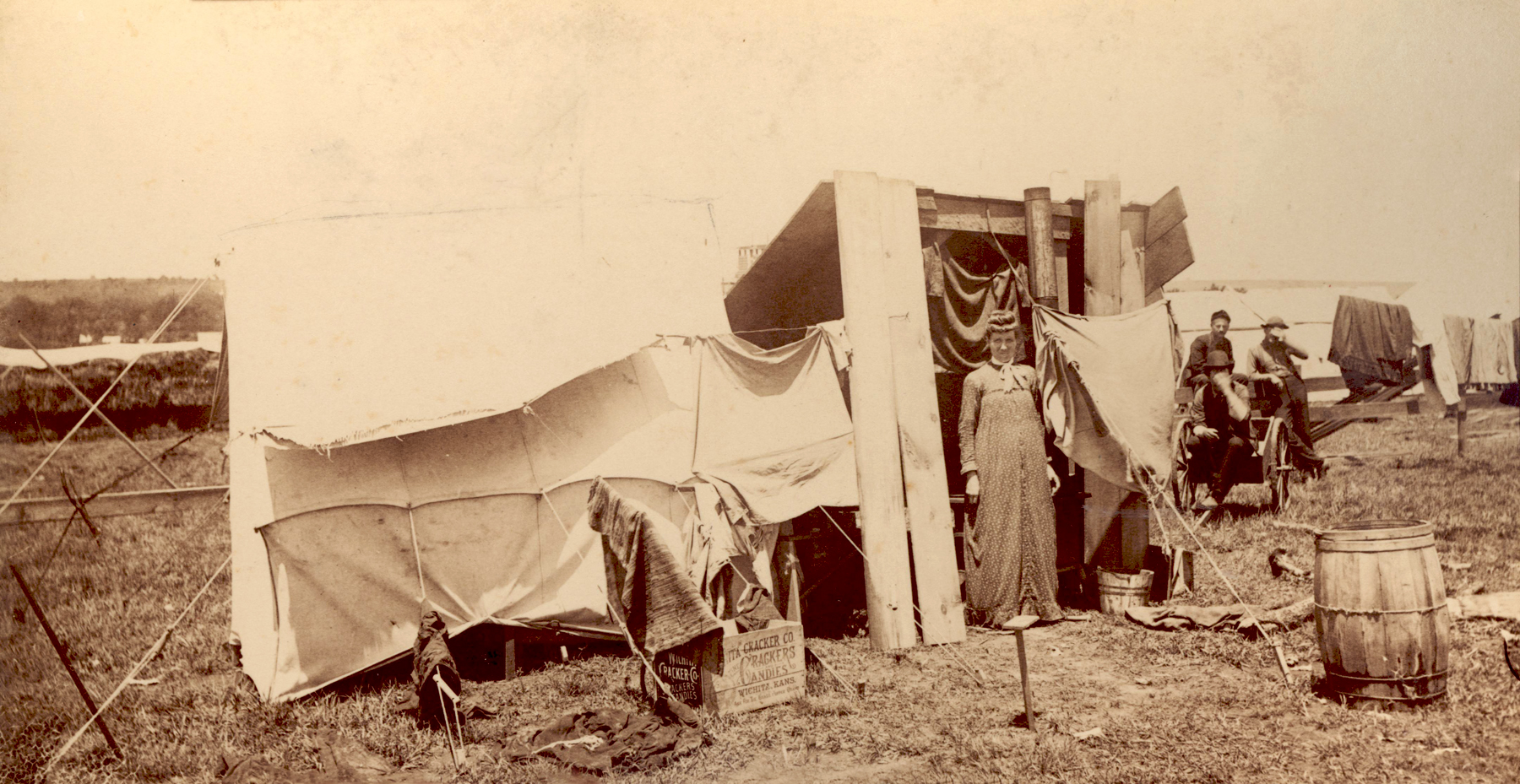

Representative of the hundreds of white women who took part in the land runs are Nannita Daisey, Elva Ferguson, Kate May, Laura Crews, and Lucy Davis. During the Land Run of 1889 the daring, single, newspaper reporter Daisey jumped from a train to stake a claim near Edmond. Ferguson, wife and mother of two young children, witnessed three land openings before the family settled in Watonga. May followed her husband to Oklahoma City after he made the run in 1889. Widowed by 1893 May participated in the Cherokee Outlet Opening. Crews and her brother made the Cheyenne and Arapaho Run but did not file a land claim. However, they did stake a claim in the 1893 opening. A determined Davis and a lady friend from Winfield, Kansas, registered at Arkansas City to participate in the 1893 land opening. Both women claimed a town lot in Newkirk, to the chagrin of Davis's husband, who had refused to make the run because he believed there would not be enough land for all the claimants. Lucy Davis and her ten-month-old daughter lived in a tent until a home could be built.

African American women also participated in the land runs. Historian Jimmie Lewis Franklin states in The Blacks in Oklahoma that the exact number of African American participants in the land openings is not known. However, in 1890, one year after the Land Run of 1889, the census reported a total of 1,365 African American women residing in Canadian, Cleveland, Kingfisher, Logan, Oklahoma, and Payne counties. One of those women was Lizzie Robinson's mother, who came with other Blacks from Memphis, Tennessee, in 1889.

Oklahoma historian Arrell M. Gibson described the pioneer woman as "resourceful, inventive, creative and versatile." With those talents Oklahoma's pioneer women made their mark on the state's history, whether as mothers and homemakers or as teachers, lawyers, and politicians. They managed households and reared children from dugouts and sod houses. Their personal stories provide insight into the state's early history and capture the essence of life on the prairie and in the small towns that grew in a day. To commemorate their spirit, former Gov. Ernest W. Marland commissioned the Pioneer Woman statue, which was erected in Ponca City.