PAWNEE.

Throughout the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries the Pawnee lived along major tributaries of the Missouri River in central Nebraska and northern Kansas. Historically one of the largest and most prominent Plains tribes, they numbered ten thousand or more individuals during the period of early contact with Europeans. From the end of the eighteenth century to the present, four divisions, generally designated as bands, have been recognized. Northernmost were the Skiris, who spoke a distinct dialect of Pawnee, a Caddoan language, and formed a separate tribe. Until the early nineteenth century the Skiris lived along the north bank of the Loup River, at one time in perhaps as many as thirteen villages, but during the early historical period they occupied a single village. South of them, generally on the south bank of the Platte River but extending as far south as the Republican River in Kansas, lived the Chawis, the Kitkahahkis, and the Pitahawiratas, each of whom usually comprised one village each. The latter three groups, today generally designated the South Band Pawnee, spoke a single dialect of the language.

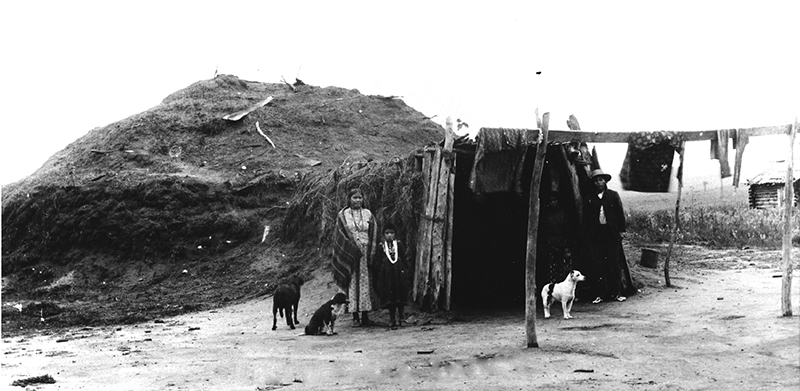

The Pawnee were semisedentary and represented the horticultural tradition on the Plains. Their life was characterized by alternating patterns of cultivation and High Plains bison hunting. The annual round of that life began in the spring when they lived in permanent villages of dome-shaped earth lodges, domiciles often housing two or more families and twenty or more individuals. During this season economic and ritual activity focused on horticulture: women prepared and planted gardens of corn, beans, and squash; men engaged in religious rituals associated with gardening. In June members of each village traveled west onto the High Plains, and for nearly three months they lived in temporary bowl-shaped shelters and hunted bison. In late August they returned to their earth lodge villages to harvest the crops and to take up again a rich, variegated ritual life. In late October or November the people again left their villages for the winter hunt, during which they lived in bison-hide tipis. In February or March the groups returned to their earth lodges to begin the annual cycle anew.

The basic unit of Pawnee social organization was the village. In the first half of the nineteenth century the village and band frequently coincided, and at different times the number of villages in a band varied from two to five or six, each comprising forty to two hundred lodges and ranging in population from eight hundred to thirty-five hundred. At an earlier period the number of villages was apparently greater and the population of each much smaller.

Governing each band or village were four chiefs (a head chief and three subordinate chiefs), who wielded considerable authority. The head chief's position, and that of others, was hereditary, but an individual could achieve chiefly status through success in war. An important symbol of the chief's office, as well as a symbol of the village itself, was the sacred bundle, a religious shrine that represented the history of the band or village. Although the chief owned the bundle, and his wife cared for it, a priest (not the chief) knew its rituals and performed the religious ceremonies associated with it. In secular Pawnee society there were other notable offices. Each chief, for example, was assisted by four warriors who carried out his orders, and he had living in his lodge a crier or herald who made announcements to the village. Chiefs and successful warriors also had living in their lodges one or more young men known as "boys," who were aides to the man of status.

Fundamental to Pawnee ceremonial life is a cultural dichotomy between religion and shamanism that was manifested respectively in the rituals of priests and those of doctors. Rituals largely dominated Pawnee life and distinguished the Pawnee people from other Plains tribes. Although both priests and doctors shared a general concern with the supernatural and attempted to control natural phenomena, what distinguished them were the differences in their objectives, the deities they invoked, and the means by which they sought to achieve their ends.

Priests (kurahus) sought to promote village welfare as mediators between the people and the deities of the heavens (stars and other celestial phenomena), where everything in the world had its origin. Priests sought good fortune and an orderly world through knowledge of the complex rituals and knowledge associated with each village's sacred bundle, a collection of symbolic and ritual objects wrapped up in a buffalo hide casing. Every village had a sacred bundle that served as a sacred object that would save the village and as an altar for its rituals. Through rituals, priests were responsible for weather, plant growth, fertility, and other generalized human concerns that for Pawnees were bountiful crops, plentiful buffalo, and success in war.

In contrast, the deities of doctors (kuraa'u') were animals, birds, and other earthly beings. Their powers were curative, but they also included the ability to mesmerize people or to bring some malady or misfortune on an individual. Among the animals and birds there was no hierarchy. Although some, like the bear, were thought to be especially powerful, all animals, and even insects, had distinctive powers that they could impart to humans. They came to individuals in dreams, usually when a person was in a pitiful state, and taught them their knowledge, "blessing them" as Pawnees say. Often, as among most Plains tribes, a single animal would bestow such power, but among the Pawnee an additional, distinctive theme is the bestowal of various powers by a group of animals in an animal lodge. Such lodges were usually located underwater or on the bank of a body of water, and in them animals of various species were said to meet, arranging themselves in the same manner as Pawnee doctors in the doctors' lodge and performing like Pawnee doctors. Typically, a young man would fall asleep beside a body of water, and an animal would mesmerize him and take him below into the animal lodge, and the animals would invariably pity the young man and bestow their powers on him.

Over the course of the nineteenth century the Pawnee people were subjected to an incessant, ever-increasing interplay of destructive forces that radically changed their lives, all forces that were largely the result of the rapidly increasing influences of an expansionist United States. One was white emigration and transcontinental travel that went directly through traditional Pawnee territory. As the century progressed, emigration swelled, putting increased demands on the region's limited natural resources, that is, on the buffalo and other game required for food, on the pastures and other forage needed by horses, on the wood used for houses and for fuel, and, ultimately, upon the very land the Pawnee considered their own. Simultaneously, the forced removal of eastern tribes to land west of the Mississippi River added approximately 30 percent to the Native population of the eastern Plains and created even more subsistence demands on an already economically uncertain environment. With the increase in population came pressure on the Pawnee to relinquish large portions of their territory. In 1833 the four Pawnee bands, now treated by the government as a single tribal entity, ceded their lands south of the Platte River. Finally, in the 1857 treaty signed at Table Creek, Nebraska Territory, they accepted a small reservation on the Loup Fork of the Platte River, together with monetary and other economic provisions.

White emigration and Indian removal from the East brought devastating disease and warfare to the Pawnee and, more widely, to Indian life on the eastern Plains. Throughout the century a series of epidemics took a steady toll on the Pawnee population. In 1849, for example, cholera killed more than a thousand individuals, and in 1852 a smallpox epidemic, only one of many, reduced the tribe. Equally demoralizing was the loss of life from the unremitting attacks of their enemies, particularly the Sioux. The Pawnee had always been at war with most Plains tribes. Their only friends had been the Arikara, Mandan, and Wichita. They had also enjoyed intermittent peace with the Omaha, Ponca, and Oto, but only because they had inspired fear in them. With all others, particularly the large nomadic ones, there was perpetual conflict. After the treaty of 1833, however, the Pawnee gave up their weapons, renounced warfare, and agreed to take up new lives as agrarians, ostensibly to be protected by the federal government. The effect of this new life of dependency, combined with severe population loss from disease, left the Pawnee vulnerable to their enemies, primarily the Sioux, who vowed a war of extermination. For forty years after that treaty the weaponless and unprotected Pawnee endured constant attacks by Sioux war parties that inflicted a major loss of life. Finally, in 1874 the tribe began a two-year removal to Indian Territory, and there the Pawnee began new lives.

Pressure from the Sioux motivated the Pawnee to furnish scouts who served with the U.S. Army during the Plains Indian wars. The first enlistment comprised ninety-five scouts who served in the 1865–66 Powder River Expedition against the Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapaho. Shortly afterwards, a battalion of four companies of Pawnee scouts was enlisted to protect workers engaged in constructing the Union Pacific Railroad's transcontinental line through Nebraska and Wyoming during the late 1860s. In 1871 the scouts were mustered out, but again during the 1876–77 campaign against the Sioux and Cheyenne, scouts were enlisted.

From the treaty of 1833 until their move to Indian Territory the Pawnee were also under progressively increasing pressure to change from their traditional lifestyle to the new agrarian one represented by white farmers. Missionary efforts began in 1831, with the arrival of the Presbyterians John Dunbar and Samuel Allis. Government farmers soon settled among the Pawnees as well, and Allis opened a school for Pawnee children. Until 1860, however, most of these efforts at changing Pawnee life were desultory and ineffective. After the tribe settled on a reservation, however, government efforts at acculturation intensified. Conscious of the gradual disappearance of the buffalo, many Pawnees were becoming more amenable to an agricultural way of life by individual families and to education. Nevertheless, right up to their removal from Nebraska, they still clung to their village life. Most people lived in earth lodges, cultivated corn, beans, and squash in the traditional manner, and depended on the buffalo for part of their subsistence.

In 1874 the Pawnee gave up their Nebraska reservation and over a three-year period moved to Oklahoma. Meanwhile, the Pawnee agent had selected a new reservation for them on Cherokee land between the forks of the Arkansas and Cimarron rivers, south of the Osage Reservation. The bulk of this land comprises contemporary Pawnee County. After tribal leaders accepted the land, the tribe, with a population of some two thousand, settled into a pattern of life much like the one they had known in Nebraska. Each band settled on a large, separate tract of land assigned to it and, initially, began cooperatively to farm the band tract. For a short time an attenuated form of their old village life was maintained; chiefs, priests, and doctors continued to organize Pawnee social, economic, and religious life. Nevertheless, many younger, progressive Pawnees soon began to move onto individual farms during their first decade in Indian Territory. By 1890 most of the Skiris and a large proportion of the Chawis lived in houses on their own farms, dressing like contemporary whites, and speaking English in daily life.

By the close of the century, then, Pawnee culture fundamentally had changed. The symbols of the old were now by and large vestiges. Village life had been replaced by life on individual farms; a mixed horticultural-hunting subsistence pattern had given way to agriculture and government rations; the authority of chiefs had been replaced by that of the agent; and religious ceremonies and the knowledge of sacred bundles was rapidly disappearing as the priests who possessed that knowledge died and no successors came forward. Doctors' dances were to continue in attenuated form for several decades, but after 1878 the protracted late-summer doctors' dance, in which the doctors demonstrated their powers, ceased.

During the early years on their new reservation the Pawnees tried to provide for themselves by farming. However, the produce proved inadequate, because natural misfortunes occurred. Since no more than one-third of the reservation was suited for cultivation, the government tried to develop a stock-raising program, but that ended in failure in 1882. In that same year, as a result of the Allotment Act, individual families were encouraged to relocate on individual farms. In 1890 most Skiris and a large proportion of Chawis lived in houses on their own farms, and during the decade most Pitahawiratas and Kitkahahkis moved onto their own land as well. At the same time agency officials relentlessly attacked many Pawnee social customs: polygamous marriages, dances, gambling, and feasting. By 1890 Pawnees were relatively prosperous materially and had adopted most of the material culture of their white neighbors. However, over the first three decades of their new residence in Indian Territory, the Pawnee people experienced poor health, coupled with inadequate sanitation and health care. As a result, the population reached a record low of 629 individuals in 1901 and did not begin to recover until the 1930s.

In the same period the Pawnee Agency established the Pawnee Industrial Boarding School, but it could accommodate no more than one-fourth of the tribe's school-age population. In 1879, when the government began establishing off-reservation boarding schools, many Pawnees attended Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania and Hampton Institute in Virginia. When Chilocco and Haskell schools opened, Pawnee children were sent there, too. By 1889 most school-age children were enrolled in the agency or off-reservation boarding schools.

Beginning in 1906 the Pawnee no longer had a tribal government, and they remained unorganized politically during the first three decades of the twentieth century. The Pawnee tradition of hereditary chiefs was still an honored one, and so the chiefs continued to act for the tribe in dealing with U.S. government officials. In the 1930s the situation changed when the Indian Reorganization Act and the Oklahoma Indian Welfare Act ushered in a nonassimilationist program that sought to give tribes legal status and economic resources to continue their existence. In 1936 the Pawnees adopted a tribal constitution that established two governing bodies: a chiefs' (or nasharo) council comprised of eight individuals having hereditary rights to chieftainship, elected every four years; and a business council made up of eight individuals elected every two years. The business council was to act for the tribe and transact its business, but the chiefs' council was largely a symbolic entity.

Shortly after reorganization, in 1937 Pawnee leaders began a three-decade-long effort to regain the Pawnee Reserve lands surrounding the agency, then on the eastern edge of the town of Pawnee. Ownership was returned to the tribe in 1968, and two tracts were later added. In 1962 the tribe also acquired the former Pawnee Indian School, a complex of stone buildings that had been vacant for twenty years. In 1980 a tribal roundhouse, modeled on the traditional Pawnee earth lodge, was built to serve as a social center for dances and other events. All of those acquisitions have provided the Pawnee Tribe, today the Pawnee Nation, with both a physical and symbolic locus for tribal administration and social identity.

What Pawnees had not regained in a changing world was their former independence. In 1891 the majority of the tribe adopted the ghost dance when it spread among Plains tribes, promising a return to their former way of life before the advent of whites. During that decade the dance was reorganized into a four-day ceremony that ended with a hand game. During ensuing years the hand game, formerly a men's gambling game, became an integral part of the ghost dance, with hand games alternating with periods of dancing to ghost dance songs. Although at first a religious ritual, over the course of the twentieth century it transformed into a social event that lost its original significance. By mid-century, and continuing through the present, there were hand games at least once or twice a month to celebrate birthdays and military furloughs as well as to raise funds for organizations.

The ghost dance also served as a stimulus for the revival of many features of traditional Pawnee culture: the reconstruction of many former men's societies, attenuated versions of the doctors' dance, older dances like the iruska, or war dance, and many games. During the same late-nineteenth-century period Peyotism, now the Native American Church, was introduced to the Pawnees. A small but active group of Pawnee families embraced it and have maintained a membership that continues today.

Most of the revivals of traditional Pawnee life, such as the doctors' dances and the reformed men's societies, had ceased by 1930, but dances like the iruska and young dog dance continued. In 1946 two Pawnee veterans, with tribal support, sponsored a homecoming celebration to honor World War II veterans. Focused around war dancing, the Pawnee Indian Homecoming Celebration, sponsored by the Pawnee Indian Veterans Association, continues as an annual, four-day event held in early July. Pawnees from throughout the United States return home to join with their relatives to celebrate the event. Most of the attendees camp during the celebration and visit with relatives and old friends, and dance. Other contemporary events include also dances, particularly the Veterans Day and Memorial Day observances.

Today the Pawnee Nation flourishes in the area of its former Indian Territory reservation. The Pawnee Reserve is an expanding seat of tribal administration. New departments and new services are represented by new buildings and renovation of older ones. Among the administrative units are the tribal offices, a senior citizens' center, a tribal court, a tribal police department, a library and educational center, and the Bureau of Indian Affairs office building that is leased to the government. The former Pawnee Hospital is now housed in a new, multimillion-dollar health facility, and the tribe has a new gymnasium for promoting better health. Other tribal businesses include a smoke shop on the reserve and a new truck stop with restaurant on tribal land adjacent to the Cimarron Turnpike. With those and with other planned development projects the Pawnee Nation has entered an unprecedented period of prosperity.