The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture

PUBLIC LIBRARIES.

In the United States public libraries had their start in the 1700s in urbanized New England. Reportedly, books arrived in North America in 1629. At first books were held in the hands of the wealthy, and the general populace had no access to reading material other than perhaps the Bible. Before public libraries were established, social and club libraries existed, but they required members to subscribe. Those libraries failed to meet the needs of the general public, who could not afford the subscription fee.

With the rise of population, the growth of common (public) schools, and the evolution of institutions of higher education in the United States, the public realized that books should be accessible to all. Many social philosophies influenced the ideology of a public library. Following the American Revolution government leaders recognized the need for an enlightened citizenry. Religious leaders believed that reading promoted morality. Public libraries would enhance adult education, provide vocational and technical studies, serve the self-educated, and help assimilate immigrants into American culture. By definition, a public library exists through the levy of municipal taxes, is governed by a board of trustees, serves as a repository for books, newspapers, magazines, and journals, and is free to the public.

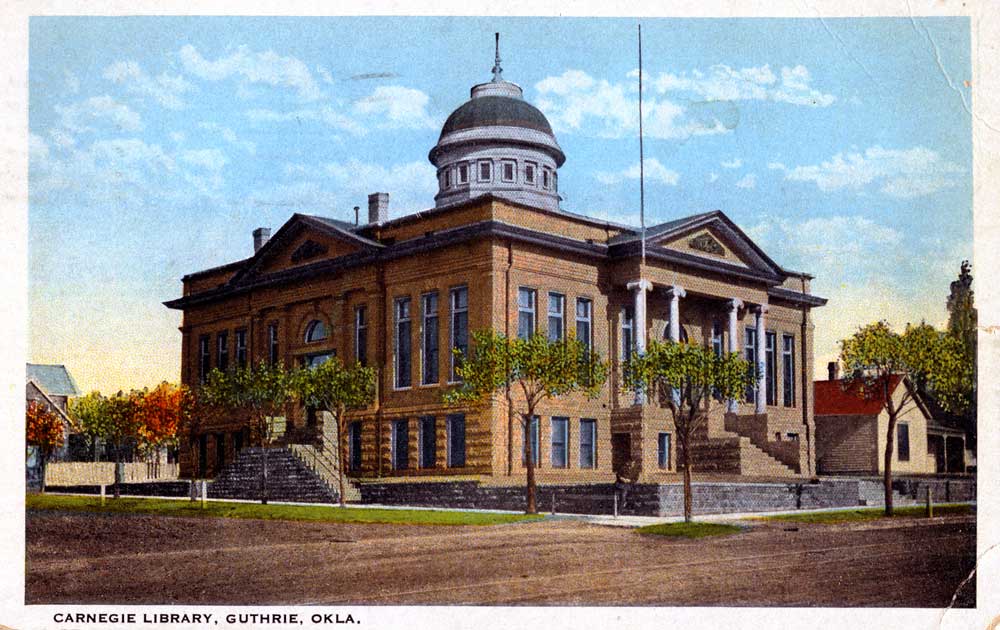

In Oklahoma, Guthrie has the distinction of having the first public library. When Oklahoma Territory was established by the Organic Act of 1890, Guthrie was designated as the capital. Territorial statues of 1901 and 1903 required that a library be established. A library in Guthrie was established in 1901, and a library in Oklahoma City opened in August 1901, with Marian Rock as librarian. She earned fifty dollars a month. Before 1907 statehood the area of the future state of Oklahoma was known as Oklahoma and Indian territories. The first free library in Indian Territory existed in Chickasha. Through the efforts of the Sorosis, New Century, and Chautauqua women's clubs that library was dedicated on March 23, 1905.

Generally, most public libraries in Oklahoma were instigated by women's clubs. In addition, civic leagues, men's clubs, and ministers helped communities to fund and furnish libraries. Initially, small collections of reading material were housed in city halls, courthouses, business establishments such as furniture stores and newspaper offices, and churches until a public library building could be erected. At 1907 statehood Oklahoma had seventeen publicly accessible libraries. The number rose to forty-nine in 1922 to seventy in 1937. Twenty-six of Oklahoma's seventy-seven counties were without public libraries in 1937.

In addition to the funding revenue from local tax levies, Oklahoma libraries received grants from philanthropists Andrew Carnegie and Julius Rosenwald. During the Great Depression federal money channeled through the Works Projects Administration (WPA) to Oklahoma, funding the erection of ten new libraries, reconstruction or repair of five, and construction of additions to two. The federal Public Works Administration (PWA) also provided funding for a library in Ponca City in 1935.

During the Jim Crow era, segregated libraries were established in locations having large populations of African Americans. Oklahoma Session Laws regarding public libraries was revised in 1911 to mandate the establishment of a separate library and reading room in cities of the first class whose African American population exceeded one thousand. In 1937 communities having segregated libraries included Claremore, El Reno, Muskogee, Oklahoma City, Tahlequah, Tulsa, Okmulgee, Ponca City, Guthrie, Chickasha, Enid, and Sapulpa. By the mid-1940s Ardmore, Boley, Cushing, Pawhuska, Stillwater, Shawnee, and Wewoka also reported having segregated libraries. Individuals instrumental in establishing those facilities included Andrew J. Silverman, Judith Ann Carter Horton, and Cora Case Porter. Julius Rosenwald also donated money to buy books for libraries. Although most of that reading material went to school libraries, some volumes reached their segregated public libraries. Those remained segregated until the 1950s and 1960s when the Civil Rights movement brought about desegregation.

In 1919 the state legislature approved the establishment of the Oklahoma Department of Libraries (ODL), originally known as the State Library. Robert H. Wilson, state superintendent of public instruction, served as the commission's first president. Its purpose included the responsibility to give advice and to help establish public libraries, to receive gifts of money, books, and other property, to operate a traveling library, to publish lists and circulars of information, and to conduct summer schools for library instruction. Between 1919 and 1920 the commission helped establish fourteen libraries. The commission initiated the Children's Book Week and summer reading programs for children. Auxiliary services have included providing Braille material and talking books to visually challenged individuals. Between 1946 and 1948, 26,985 requests for those materials were filled.

In the past, traveling libraries provided an important service to Oklahoma's largely rural population. Small rural communities did not have the tax base to support a local public library, so the citizenry initially requested reading material through women's clubs. Beginning in January 1920 the public libraries in larger metropolitan areas provided that service. Boxes of books were sent to rural schools, the Farmers' Grange and Union, home demonstration and county agents, and women's clubs. In 1920 seventy-five of Oklahoma's seventy-seven counties participated in the program with approximately nine thousand books furnished to rural citizens. By the late 1940s the traveling library program circulated 6,923 volumes. The number of books requested through that program decreased as the more public libraries created libraries. In addition to traveling libraries, bookmobiles came into vogue around 1930; Tulsa claims to have had the first one in Oklahoma. The bookmobile served as an outreach program taking books to public areas such as hospitals, parks, and fire stations.

In addition to traveling libraries, county libraries filled a void in sparsely populated areas when limited revenue retarded the growth of public libraries in municipalities. The Oklahoma Legislature passed the County Library Law on April 13, 1929, authorizing the establishment of county libraries as independent entities or as contracting with an existing library to provide service to rural patrons. Garfield County has the distinction of having the first county library, and by the 1940s six counties had them: Alfalfa, Beaver, Garfield, Lincoln, Okfuskee, and Washington. Library service was extended to hospitals, jails, county homes, and African American libraries.

As Oklahoma's population increased and during periods of revenue shortfall, public libraries within a county would join with adjacent counties to form multicounty library systems. Patrons were allowed to borrow materials from libraries outside their county, thereby giving citizens greater accessibility to limited resources. For example, beginning in April 1960 the ODL cooperated with counties in southern Oklahoma to form the Chickasaw Library System. The counties of Johnston, Love, Murray, Atoka, Coal, and Carter formed a system that provided service to nine libraries and forty-four bookmobile stops. Circulation included not only the usual requests for books and newspapers but also included maps, cassettes, tapes, puzzles, 16mm film, film projectors, and record and tape players. The Choctaw Multi-county Library System served Pittsburg, Latimer, Le Flore, Haskell, McCurtain, and Choctaw counties. In 1972 the Southern Prairie Library System included services from Jackson and Harmon counties and offered a bookmobile, a genealogy library, and a multipurpose room. At the turn of the twenty-first century Oklahoma had 213 public libraries with eight library systems serving one or more counties.

As in the past, public libraries offer space for reading, studying, and meetings. The public continues to have free access to reference works, circulating materials, participation in reading clubs, children's reading hour, and other programs. Through the years, the services have changed and improved. Faster modes of transportation accelerated the speed in which traveling libraries were sent to rural population. Technology has improved the cataloguing process and shortened the response time to fill interlibrary loan requests. Patrons have access to computers and wireless internet inside the library and may borrow DVD's, audio books, and specialized collections in addition to print books. In the twenty-first century many books, newspapers, and journal articles have been digitized giving patrons instant access from their home computers.

See Also

CARNEGIE LIBRARIES, GREENWOOD DISTRICT, JUDITH ANN CARTER HORTON, OKLAHOMA DEPARTMENT OF LIBRARIES, OKLAHOMA FEDERATION OF WOMEN'S CLUBS, ANDREW J. SMITHERMAN, WOMEN'S CLUB MOVEMENT, WORKS PROGRESS ADMINISTRATION