QUILTING.

Roderick Kiracofe, historian of quilting, has noted that "quilts, like diaries, are an accumulation of bits and pieces of the maker's life, a repository of ideas, hopes and feelings." As with all things, a quilt reflects society as a whole and also reflects its individual maker.

Oklahoma's quilts readily illustrate the state's diversity, as most cultures have had quilters within their communities. Quilters have included males, females, the elderly, the young, American Indians, African Americans, and a myriad of ethnic and occupational groups. For instance, the collections of the Oklahoma Historical Society include a Civil War–era quilt made by Stephen A. Lewis, a Union soldier, while he recuperated from wounds sustained in battle; Lewis subsequently moved to Pryor, Oklahoma Territory, bringing along his quilt.

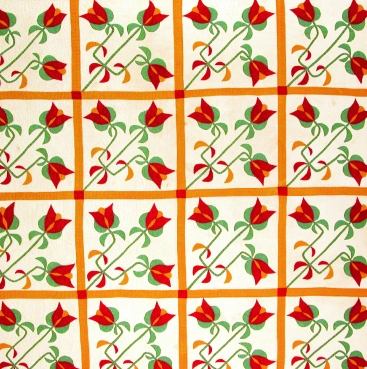

In Oklahoma, as in the nation, quilts reveal diverse cultural, economic, social, and political concerns. Oklahomans have produced utilitarian quilts as well as fancy artwork quilts. Many were of the pieced variety, that is, small pieces of fabric were stitched together to make a pattern or picture; others were large, single pieces of fabric that were then appliquéd or embroidered. As with all things, the art of quilt making has evolved through the ages. For example, in the 1890s through the early 1900s, the Victorian Era, "crazy quilts" became popular. These were patches of satin, silk, and lace, fairly costly fabrics, to which the quilter then applied embellishment such as embroidery and trim. However, during the Great Depression of the 1930s many Oklahomans made simple quilts of flour and feed sacks. The quilter often used small pieces of fabric from worn-out clothing. Everything was used and nothing wasted. Thus, quilts visually reflect the economic conditions and values of those eras.

Traditionally, the art of quilting was generally passed down from generation to generation. Until recent decades mothers were expected to teach their daughters the skills of handwork and sewing, including quilting. It took massive time and energy to make a quilt by hand, but the invention of the sewing machine in the mid-1800s made the process less time consuming. After the Kansas City Star, the Daily Oklahoman (Oklahoma City), and the Oklahoma Farmer-Stockman (Oklahoma City) newspapers began to publish patterns for pieced-block quilts in the 1920s and 1930s, quilters throughout the Midwest and also in Oklahoma began to use standard, printed patterns. Sometimes without even recognizing it, they would record bits and pieces of their daily personal lives, hopes, and dreams with their stitches. Quilts have been used to express opinion, folklore, and personal creativity, aspects of life that were often recorded in the pages of a quilter's diary as well as in a quilt.

Quilts also represented community values and commitments. Schools, churches, and hospitals often raffled them off to raise money for a worthy cause. The Mennonites and the Amish in Oklahoma make highly prized quilts. Oklahomans made celebratory quilts, protest quilts, support quilts, patriotic quilts, and remembrance quilts. They were also made to record history on a personal or family level, or more broadly, on a statewide or national level. The collections of the Oklahoma Historical Society, for example, include the "Oklahoma Historical Quilt," an appliquéd and embroidered work created by Camille Nixdorf Phelan and presented to the society in November 1935.

Since the 1960s there has been a renewed look at quilting as an art form and at quilts as textile art. In 1984–88 the Oklahoma Quilt Heritage Project, under the auspices of the Central Oklahoma Quilters Guild, Inc., and the Oklahoma State Quilters Guild, Inc., surveyed and documented more than four thousand that were either made in or brought to Oklahoma before 1940. Oklahoma has a rich heritage hidden within its quilts.