The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture

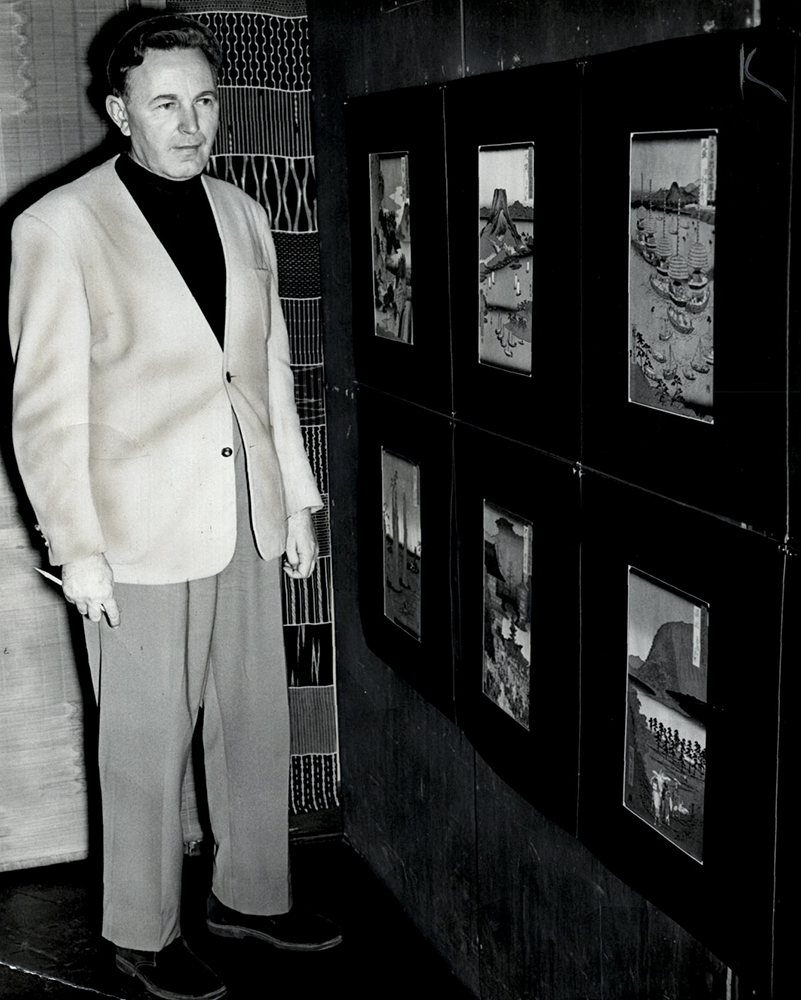

GOFF, BRUCE ALONZO (1904–1982).

Born June 8, 1904, in Alton, Kansas, to Corliss Arthur Goff, a jeweler, and Maude Furbeck Goff, a schoolteacher, Bruce Alonzo Goff lived with his family in several towns in Kansas, Colorado, and Oklahoma before moving to Tulsa in 1914. At age twelve Goff began his part-time work in the office of a local architecture firm, Rush, Endicott and Rush.

In those formative years Goff discovered Frank Lloyd Wright’s work, a significant step in his intellectual development. He was drawn to Wright’s philosophy of organic architecture, which emphasized nature and individuality, and he was intrigued by the prominent architect’s buildings. Graduating from high school in Tulsa, Goff decided not to pursue academic training in architecture. He remained with Rush, Endicott until the Great Depression began.

During the 1920s he learned much about contemporary design. He studied the work of European expressionist architects while designing buildings for oil-rich Tulsans. His most significant achievement during these years was the 1926 Boston Avenue Methodist Episcopal Church, as a collaborative effort with Adah Robinson, his former art teacher and client, who designed the decorative motifs. The building, with its 255-foot tower terminated by an ensemble of copper and glass fins, has been designated a National Historic Landmark as one of the most significant churches of the twentieth century. Further, Goff also began a lifelong interest in painting and music. Influenced by avant-garde European movements and artists such as Maxfield Parish, Goff developed a serious avocation, abstract painting. In addition, his abiding interest in classical music led him to explore the similarities between the elements of composition in music and architecture.

Goff practiced and taught in Chicago during the 1930s and served in a U.S. Navy construction battalion in Alaska during World War II. He practiced briefly in San Francisco before returning to Oklahoma in 1947 as a professor of architecture at the University of Oklahoma. Later that year he was appointed chair of the School of Architecture, a position he held until 1955.

From the postwar years until the end of his career, Goff’s architectural expression became increasingly diverse. Central to his philosophy was the uniqueness of both client and building site as primary determinants of design. He would frequently ask clients about their favorite color and incorporate it into the design as a way of personalizing their environment. Yet there are common principles that establish a sense of continuity and inform us of his ideals. A prominent design principle evident in his work is the utilization of alternative typologies of geometry to define form. He would often derive a floor plan from a primary geometric form, such as a circle, triangle, or hexagon, with the interior volume defining a vertical axis. The interior space would then be magnified by an open plan with visual extensions into adjacent spaces. He also often designed “built-in” furnishings to be an integral part of the architecture. Natural light in Goff’s buildings frequently comes through skylights or clerestories that offer views of clouds and sky. Facades are highly articulated and rich in pattern, texture and color. Many Goff houses have exaggerated eaves with a thin edge that evokes a feeling of lightness. He also used interior or exterior pools to reflect and embrace the natural world.

Goff executed many residential, commercial, and church designs in Oklahoma. Included are Shin’enKan near Bartlesville, Riverside Studio on Riverside Drive in Tulsa (listed in the National Register of Historic Places, NR 1000656), the Cox House in Boise City (now part of the Cimarron Heritage Center), the Celestine Barby Studio in Beaver, and the Hopewell Baptist Church in Edmond (NR 2001018). The Gene and Nancy Bavinger House, designed in 1950 for a rural site in Norman, Oklahoma, is regarded a significant example of his mature work. The plan is a logarithmic spiral with exterior walls of rubble stone inset with blue-green glass cullets. The spiral wall appears to emerge from the earth and wrap around a central mast rising more than fifty feet in the air. The roof is a warped plane suspended from the mast by airplane struts. The space within is dynamic: the dimension between floor and ceiling expands, but the dimension between spiraling walls contracts. “Rooms” are circular platforms at different levels, accessible by stairways cling to the spiral’s interior wall. The lowest platform, located at the wide part of the spiral near the entry, is a conversation area raised slightly above the floor. Above are platforms that function as sleeping areas and an uppermost platform that is a glass-enclosed studio. Collectively, this ensemble of platforms establish a dominant rhythm that ascends upward.

In 1955 Goff relocated his practice from Norman to Bartlesville, Oklahoma. He later established his office in Kansas City for several years before moving to Tyler, Texas. During the last three decades of his career he continued to design highly original buildings from Florida to California and Minnesota to Texas, although there are more of his buildings in Oklahoma than in any other state. His last project, the Japanese Pavilion of the Los Angeles County Art Museum, has pleated, translucent walls like insect wings folded over a base of rubble stone. Built next to the La Brea Tar Pit, the design has animalistic qualities that resonate with pathos for the prehistoric creatures buried beneath the black, reflective surface. The museum building, with its suspended roof attached by cables to a projecting horn-like structure above, is a fitting tribute to the life and career of a true American genius. Bruce Goff practiced in Tyler until his death on August 4, 1982.