CORN.

Far in advance of the arrival of Europeans, the Native peoples of North and South America had cultivated varieties of corn or maize for millennia, both as a staple for their diets and as a significant part of their cultural and religious rituals. Contact between Europeans and American Indians served colonists well in that native corn was a gift to humankind thereafter. Once corn cultivation techniques were learned from the Indigenous population, colonists mixed that knowledge with their experience and subsequently moved into the interior. There, on a series of frontiers, they developed additional agricultural skills. When settlers migrated into the Great Plains, many brought corn culture as part of their baggage.

In the Indian Territory (present Oklahoma) corn was a principal crop among the Five Tribes. For example, both the Choctaw and Creek raised abundant corn crops soon after arriving in the West. The Choctaw exported corn for manufactured items, and the Creek sold their surplus crop to the troops at Fort Gibson or to contractors who supplied other immigrant tribes.

Negotiations between the U.S. government and the Cherokee Nation in 1893 led to the opening of a portion of Cherokee lands to non-Indian settlement. A vast land rush brought homesteaders to the Cherokee Outlet, located across the northern tier of present Oklahoma, to claim sites suitable for farming. Seven Oklahoma Territory counties were formed from the Outlet and were occupied by settlers, many of whom were often short of capital, implements, and draft animals.

Corn cultivation, destined to extend across Oklahoma, began immediately in the former Cherokee Outlet. Crop yields suffered from the exigencies of the semiarid climate where rainfall was scant (corn requires thirty-five inches of rainfall annually for success) and temperatures varied greatly from summer to winter. An abundance of precipitation was found in eastern sectors of Oklahoma but far less fell along and beyond the 100th Meridian. Farmers in Old Greer County (present Greer, Harmon, Jackson, and part of Beckham counties) led Oklahoma Territory with a harvest of 156,969 bushels in 1890.

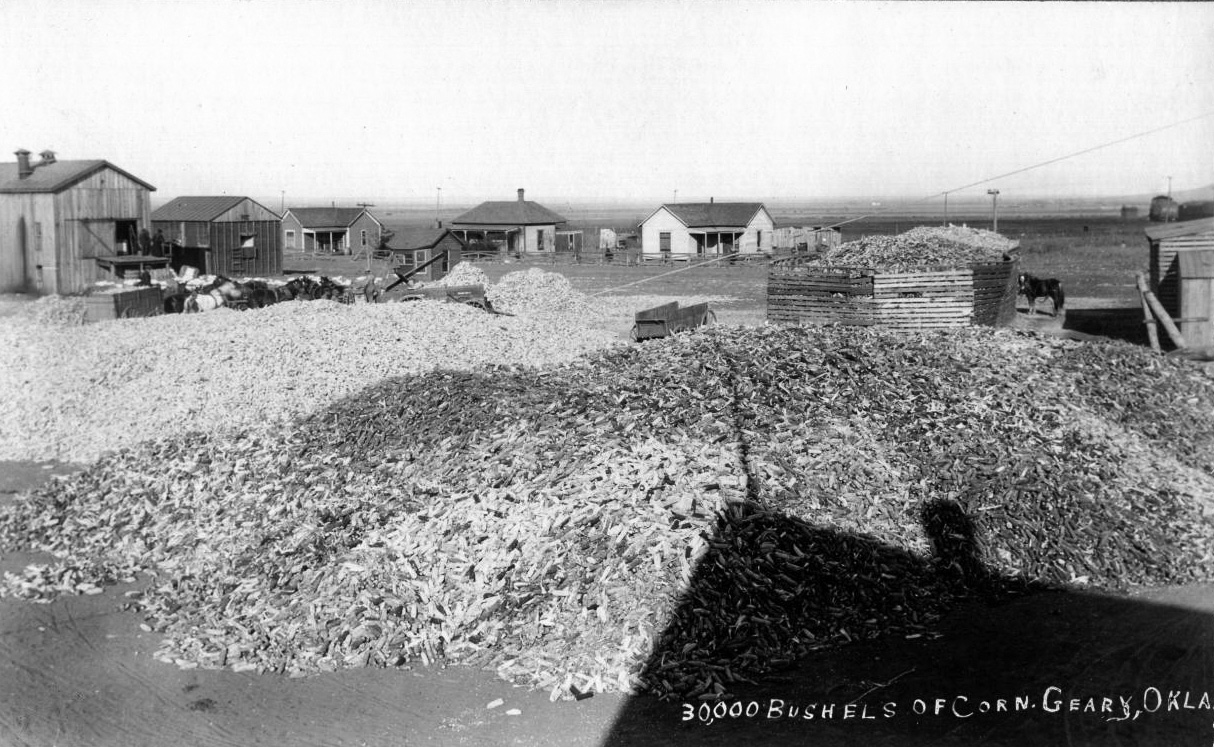

By the late 1890s corn surpassed all other Oklahoma crops in total acreage sown, only to fall behind wheat and cotton production in years following. Corn competed for cotton as a cash crop, but corn planting nevertheless spread to the southern, central, and southeastern sectors of Oklahoma. Grady and Caddo counties led in corn production soon after 1907 statehood, with harvests of 3,861,270 and 3,720,109 bushels, respectively. Despite rising agricultural opportunities, farm tenancy increased to more than 80 percent in 1910. For some farmers broomcorn presented profit potential, and corn vied with it. In 1915, during the early stages of World War I, Oklahoma corn production rose to 104,135,000 bushels with a value of nearly $60 million.

Corn production faltered during the Dust Bowl era of the Great Depression. One resident of Eva in Texas County, Oklahoma, lamented in June 1935 that she found herself and family in "the dust-covered desolation of No Man's Land . . . with handkerchiefs tied over our faces and Vaseline in our nostrils." Corn brought twenty-seven cents per bushel in 1931 but fell four cents lower the next year. Muskogee County led the state in production with 746,400 bushels in 1933.

During the Depression many farmers gave up and left the state. They were memorialized in John Steinbeck's novel The Grapes of Wrath, along with the crop they attempted to grow; page one reveals that "the sun flared down on the growing corn day after day until a line of brown spread along the edge of each green bayonet." Those agriculturists who remained in the state persevered against great odds. The 1950s presented another drought cycle. Fortunately, greater forage amounts prevented a repeat of the hardships of the 1930s, and the corn yield per acre remained relatively high. In 1950 Muskogee County again led the state by producing 1,016,800 bushels of corn, followed by Garvin County with 884,800.

Cattle and corn have always been compatible. By the 1970s feedlots appeared in western Oklahoma, and cattle and hogs (poultry, similarly, in the south and east) were confined, corn-fed, and sold to meat-packers. Thus, corn farmers benefited, and part of their success can be understood because of extensive irrigation practices in northwestern Oklahoma. So great was their dependence upon irrigation in the Panhandle that most of the corn produced there can be traced to the availability of this resource. From 1970 through the end of the twentieth century Texas County in the Oklahoma Panhandle dominated the state's corn harvest, with yields ranging from 2,397,000 bushels in 1980 to 16,180,000 in 2000.

Oklahoma corn production waned toward the beginning of the twenty-first century, suggesting a possible decline in future corn harvests. In 2002 corn ranked tenth among Oklahoma's agricultural commodities, and the state was twenty-sixth nationally in corn production. Exorbitant cost of fertilizers (a necessity for corn crops), the high price of fuel for machinery, and the rise in the cost of natural gas (which provides power for irrigation pumps to coax underground water to the surface) all have led some Oklahoma corn farmers to rethink their planting, maintaining, and harvesting of the American Indians' gift to humankind.

See Also

BROOM FACTORIES, CATTLE INDUSTRY, DROUGHT, FARMING, GREAT DEPRESSION