The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture

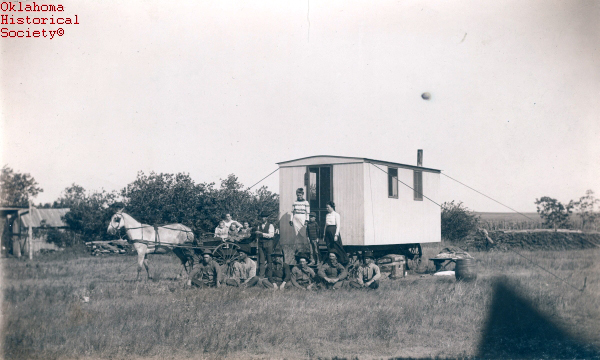

FARMING CULTURE.

In national and state mythos, if no longer in demographic fact, Oklahoma is a rural state. A vital part of that rural image and self-image is the role of farming and farming culture. Farming in Oklahoma has long been a cultural system as well as an economic one. For many rural Oklahomans, farming is a cherished way of life as well as a livelihood. At the turn of the twentieth century, in fact, many more live to farm than farm to live.

Oklahoma agricultural crops have historically included corn, cotton, winter wheat, wheat hay, oats, milo maize, soybeans, sorghum, broomcorn, peanuts, sweet potatoes, alfalfa, cowpeas, and wild hay. Other farm products have included poultry, cheese, milk, eggs, butter, and various fruits and vegetables. Many Oklahoma farmers raise livestock (cows, pigs) as well as crops. Historically, cotton and corn gave way to winter wheat as the state's primary crop.

The number of Oklahoma farms peaked at 213,325 in 1935 and were down to 72,000 by 1980. In 1920 Oklahoma's farm population was 50 percent of the state total, and by 1950 it was down to 25 percent. By 1997 only 33,060 listed farming as their main occupation; 55 percent earned their primary income outside farming (as so-called "sidewalk" and "suitcase" farmers), attesting to the value of farming in their lives and in the continuity of the family. By the 1990s farming enterprises were largely managed by large operators.

Winter wheat farming will illustrate the culture(s) of Oklahoma farmers. Under the designations of "Unassigned Lands" and "Cherokee Outlet," the northwest quadrant of Oklahoma was settled in land runs by descendants of largely German, Czech, English, and Scotch-Irish ancestry. The highly successful winter wheat "Turkey red" was originally brought to Oklahoma by Mennonite Germans from Russia during the reign of Nicholas II. The characteristic community form of the American midwestern/plains region was that of the Western European Einzelhofsiedlung or "open-country neighborhood" of widely dispersed individual farmsteads; in America the immigrant farmers faithfully continued the Western European practice. Oklahoma wheat-farming culture is a local variant of grain-farming culture throughout the North American Great Plains.

Wheat-farming culture is built around the annual cycle of summer-long plowing, late summer fertilizing and planting, winter and spring preparation of farm implements, and late spring/early summer harvesting. Harvest is the once-a-year "paycheck" that cannot be counted on until the wheat is in the grain elevator.

Core cultural values and attitudes include hard work, personal and family self-reliance and self-sufficiency, friendliness, and local control of civic affairs. The value of personal individualism is subordinated to the family and the farming enterprise. Although the sense of community is valued, it exists most noticeably in times of crisis, such as a fire or flood, during which people give generously to help restore the affected ones to independent living. Aided by the latest farm technology, farm families exert mastery upon their environment, yet they also have a fatalistic attitude toward nature and toward the natural disasters, including flood, drought, tornado, and blight, that can devastate or end life.

Land itself is regarded less a commodity than as sacred dirt, something to be worked as a trust and passed on to the next generation. Health is defined not as the presence of symptoms or disease, but as the ability to work, to perform one's family and farm roles. Traditionally, there was a clear, gendered division of labor on family farms. The men's domain was largely outside the house, and women's domain largely, though not entirely, lay within the house. Exceptions to the latter were milking cows, raising chickens, and tending the garden. The farm wife was often the accountant. Everyone, children included, was expected to contribute to the success of the enterprise.

Politically, Oklahoma wheat farmers tend now to be conservative. This has not always, however, been the case. Prior to World War I many farmers became radicalized, even socialist. Cultural contradiction abounds. At the end of the twentieth century Oklahoma wheat farmers often relied on federal subsidies yet at the same time prized independence from government control. Farms often had an "equipment graveyard" from which farmers cannibalized parts to repair their own implements and thereby retained their freedom from dependence on others.

Change has long characterized farming culture, from the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl through the farming crisis of the mid-1980s. This crisis, characterized by depressed values of land, wheat, and cattle, showed farming-culture virtues to have limits. The values of local control and self-sufficiency clashed with the overwhelming influence of national and international political economy. Steeped in an ethic of personal responsibility, many farmers blamed themselves for failure to exert influence far beyond their control. The value of private solutions, even to public problems, led to withdrawal and isolation, if not depression and suicide. Often social support, ranging from church to informal coffee group, was withheld and withdrawn in crucial times. In short, change remains a constant challenge to the persistence and integrity of farming culture in Oklahoma.