KU KLUX KLAN.

Although the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) did not officially invade Oklahoma until 1920, the organization's reputation preceded it by fifty years. Initially the Klan had emerged from the confusion of Reconstruction in the Deep South. In the 1915 movie Birth of a Nation, D. W. Griffith characterized the KKK as the savior of the Reconstruction South from evil carpetbaggers and the stereotypical African American. In 1866 Confederate Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest had reportedly formed the original Klan in Tennessee. The first Klan grew rapidly, having 550,000 members by 1869. The group focused on African Americans as people and not as lawbreakers. In 1869 General Forrest disbanded the Knights, claiming that undesirables within the fraternity had perverted its ideals and were driving out the better members. At the same time, Congress passed legislation banning the group and the use of the secret disguise for intimidation purposes.

Social conditions in the early 1920s made Oklahoma appear to be a fertile field for a KKK membership drive. The young state's population had shifted from an almost completely rural composition in 1900 to 30 percent urban in 1920. Urbanization produced crime and other changes that upset many traditionally moralistic rural residents. Oil boomtowns and the "flapper decade's" changing social consciousness produced many vices, including bootlegging, prostitution, and gambling, that upset many upright, church-going citizens. Socialists, Industrial Workers of the World, and other groups considered radical mustered many votes prior to 1920; politically conservative Oklahomans worried that the growing communist movement would gain a foothold in their state.

Although Oklahoma had a diverse population gathered from all parts of the world and the nation, many white residents, especially in the southern parts of the state, had strong ties to the southern culture that had produced the original Ku Klux Klan. Midwesterners with stringent religious beliefs and strong moral consciousness also had migrated to Oklahoma. Into this environment neatly fitted the Klan's beliefs and actions, aimed at preserving rural, white culture and Protestant Christianity and on attacking perceived threats to the racial status quo.

A fearful atmosphere pervaded much of the nation in the years around World War I, and Oklahoma did not escape the national plague of violence, race riots, and lynchings that marred American life. In 1921 the Tulsa Race Massacre, one of the worst in U.S. history, destroyed thirty-five blocks in the thriving African American section of town known as Greenwood.

The second coming of the Ku Klux Klan originated in Georgia in 1915. The founder, William Joseph Simmons, possessed great oratorical skills but lacked organizational abilities. In 1920 Simmons partnered with the Southern Publicity Association of Atlanta, and Klan membership soared to 100,000 in eighteen months. An early Oklahoma meeting discussing Klan membership occurred at Sifer's, an Oklahoma City candy store, in 1919. Earlier that year in Skiatook, Oklahoma, Klansmen publicly paraded during a Liberty Loan drive.

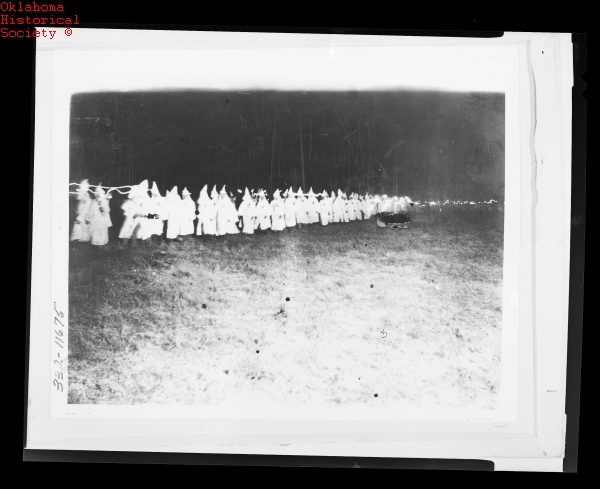

The Klan did not make a concerted national effort to recruit Oklahomans until 1920, after establishing a strong Texas membership base. Many times the recruiter would begin his work in a particular area of town by way of the fraternal orders, often carrying a letter of introduction from an affiliated lodge in the previously visited town. Secret Klan ceremonies and mysterious activities attracted many potential recruits. During this time many Klansmen also belonged to the Masonic Order, the Knights of Pythias, and other orders, and the Klan imitated some of their rituals.

By September 1921 the Oklahoma City Klan claimed twenty-five hundred members. The Tulsa Klan grew in a similar fashion, numbering two thousand Kluxers soon after the 1921 event. During the early 1920s many Oklahoma communities had numerous Klan adherents, and not infrequently, local law enforcement officers were Klan members or had strong Klan sympathies. Recruiters often successfully targeted civic leaders, Protestant ministers, and prominent businessmen. The Women of the Ku Klux Klan did not organize until 1923 but had many Oklahoma members.

Although the Klan involved its members in politics and some charity work, most historians associate the organization with acts of violence and terrorism. The Klan became the community watchdog, and when a citizen did not exemplify the Kluxers' moral standards, a midnight whipping party flogged the offender. Local law officers sometimes handed criminals over to the Klan and occasionally participated in the punishment. Members of the organization sometimes arranged these whipping parties for personal reasons, such as debt collection or competition for a girl. Although usually racially motivated, the violent act ostensibly punished a "crime" as well. The Klan also targeted European immigrants, Americans Indians, Jews, Catholics, and religious groups. On the whole, however, Oklahoma Kluxers directed most of their attention to white Protestants who had gone astray.

The Klan's power peaked in the 1920s. In 1923 the Klan built Beno Hall, an enormous, $200,000 building that dominated downtown Tulsa. The organization also played a primary role in Gov. John C. Walton's 1923 impeachment. Appalled by constant violence attributed to the Klan, Walton put parts of Oklahoma under martial law, starting with Okmulgee County, then Tulsa, and eventually the entire state. Although Walton's administration had serious troubles in addition to the Klan, his vendetta and use of martial law against that group stirred public resentment and became the primary focus of his impeachment. The trial brought unanimous votes to convict on charges of graft and of abuse of the pardon and parole powers. Walton's ordeal, however, also created a public perception of Klan lawlessness. In 1923 the Oklahoma Legislature passed an anti-mask bill aimed at curbing Klan violence.

Over the rest of the decade the Klan slowly declined in allegiance and power. Anti-Klan organizations began forming to oppose the reign of the invisible empire. Groups such as the Knights of the Visible Empire, Brotherhood of Men, Sons and Daughters of Liberty, the American Patriots, the Flaming Circle, the Royal Blues, and the Anti-Ku Klux Klan All-American Association emerged throughout Oklahoma. Threats and counterthreats of violence and retaliation became a common occurrence between 1923 and 1926. Internal disputes also weakened the Klan. In 1922 Hiram Evans ousted founder Joseph Simmons as Imperial Wizard, angering Simmons's numerous Oklahoma supporters. Charges of greed and graft, coupled with the Klan's short allegiance to the Republican Party in Oklahoma, greatly diminished Klan membership.

Nationally, a series of scandals reduced membership to a small core. Despite a brief resurgence of membership in the 1930s, and despite many isolated incidents of Klan activity, the Ku Klux Klan remained weakened and fragmented, having negligible power in Oklahoma since 1928.

See Also

AFRICAN AMERICANS, CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT, ROSCOE DUNJEE, FRATERNAL ORDERS, LYNCHING, NEWSPAPERS–AFRICAN AMERICAN, SEGREGATION, ANDREW J. SMITHERMAN, TULSA RACE MASSACRE, JOHN CALLOWAY WALTON